Invasive Species Resources

Information about invasive species that have been found in New Jersey, contact info, and how you can help

Invasive Species are organisms that are not native to a particular ecosystem but can reproduce quickly and outcompete native species once established. They can be:

- Plants

- Animals

- Fungi

- Algae

- Pathogens

Invasive species can pose significant threats to human health, agricultural resources, and the environment. Introductions to new areas can occur accidentally or intentionally through human actions. All ecosystems, whether aquatic, marine, or terrestrial, can be affected by invasive species.

Many invasive species are very common and widespread. They can be found in most of our urban, suburban, and rustic landscapes. Unfortunately, we encounter invasive species every day. It is common to see them:

- growing in our lawns and gardens (e.g., dandelions –Taraxacum officinale and white clover –Trifolium repens),

- nesting in our shrubs (e.g., European starlings – Sturnus vulgaris and house sparrows – Passer domesticus),

- and sometimes taking up residence in our homes (e.g., house mice – Mus musculus).

Other invaders have become well-established in our natural areas (parks and forests). Species such as garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), and Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), and MANY others have changed the understory of our forests. Some invasive species are very picky about where they live. These invasive species can even be host-specific, targeting only one species or a similarly related group (e.g., emerald ash borer – Agrilus planipennis and hemlock woolly adelgid – Adelges tsugae).

Native species can become ‘invasive’ too, though not necessarily in the same way. We refer to these as “nuisance” species. This happens when populations increase, ranges expand, or they become habituated to humans. Nuisance species can alter or harm landscapes, property, or constitute a health hazard when abundant. Two examples are the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and Canada geese (Branta canadensis). Though significantly diminished at the beginning of the 20th century, these animals have made an extraordinary come back. In the absence of predation and decreased hunting, deer and geese abundance has increased tremendously. Consequently, they are causing significant impacts to forests and water quality, making affected habitats vulnerable to invasive species introduction. Although many non-native and nuisance species are here to stay, the bottom line is that there is hope with proactive and adaptive management.

Invasive species can cause local or functional extinction of native species and communities. They do this by:

- Displacing natives through direct competition

- Altering habitat and community structure

- Becoming parasites

- Causing other indirect effects

One example is the disappearance of the American chestnut (Castanea dentata) in the early 20th Century. This was due to the chestnut blight, a disease caused by a parasitic fungus (Cryphonectria parasitica) native to southeast Asia. Likely introduced from shipping material, this parasitic fungus had a devastating impact on this important ecological and economic resource. Once a major component of eastern forests, loss of the American chestnut led to drastic changes in forest community composition.

In some waterbodies, newcomers (e.g., Silty pond mussels – Sinanodonta woodiana, and right-handed mud snails – Potamopyrgus antipodarum) have the potential to cause great harm to native wildlife if not contained. The silty pond mussel, for example, is a prolific and efficient filter-feeder that has been shown to greatly out compete native mussels in Europe. Generally, the following characteristics lend to a species ‘invasiveness’:

- They are habitat generalists

- Reproduce quickly

- Not subject to predation

- Fast growth

- High dispersal ability

- Phenotype plasticity (the ability to alter growth form to suit current conditions)

- Tolerance of a wide range of environmental conditions (ecological competence)

- Association with humans

- Prior successful invasions

Some invasive species are even sold for landscaping or available as pets. A few have been able to escape cultivation and find their way into our open spaces as well (e.g., Callery pear – Pryus calleryana). As a result, the composition and structural dynamics of these natural systems has drastically changed.

Other problems caused by invasive species include:

- Disruption to recreation

- Reduced water quality

- Impacts to:

- agriculture and forest production

- cultural resources

- economies and property values

- public safety

- infrastructure

There are a several pathways for invasive species introductions and eventual spread to new areas. Depending on the type of organism, the method of introduction is dependent on where it likes to live.

Invasive species introductions can be either intentional or accidental. Intentional introductions include:

-

- Planting (ex. Japanese barberry, water hyacinth)

- Release of pets (ex. Red-eared slider)

- Stocking (ex. Northern snakehead, Asian carp)

- Habitat modification for aquaculture or other purposes

Any of the above can have serious impacts on native species and the targeted habitat. For these reasons, New Jersey Fish and Wildlife (NJ F&W) has special rules in place to prevent introductions of non-native wildlife and lists the requirements for possession:

- NJ Fish Code: 2022-2025 NJ Fish Code

- NJ F&W Rule on Release of Exotics: NJ F&W Exotic Species Regs

- NJ F&W Possession of Exotic Species Requirements: NJ F&W Exotic Species Permit

- NJ F&W | Potentially Dangerous Species

Accidental introductions include:

- Hitchhiking

- seeds or propagules attached to the feet or fur of animals;

- in shipping materials;

- attached to boats, trailers, and other gear or be hidden in other materials (e.g., ship ballast, vegetation).

- Natural processes (e.g., storms, wind, wildlife)

Proper cleaning of equipment, especially in aquatic environments, is the best way to prevent invasives from invading new habitats and waterbodies.

New Jersey is a geographically unique landscape and is located near and hosts some of the busiest shipping ports in the nation. It is home to over:

- 18,000 miles of streams and rivers,

- over 3,500 lakes, reservoirs and ponds,

- and over 900,000 acres of wetlands (freshwater and tidal).

Approximately 40% of the state is forested. The State also hosts a diversity of habitat types, some of which are deemed sensitive. These include Category One designated waterways (NJ Category One Waters) and protected Natural Areas (NJ State Natural Areas).

Historically, New Jersey has experienced nearly 400 years of intensive land use change. Yet, it still harbors distinctive endemic and globally rare species populations. New Jersey has more than:

- 2,100 species of native plants;

- Over 800 native wildlife species;

- Of these, 356 plant and 83 wildlife species are threatened or endangered.

Unfortunately, more than 1,100 non-native species are already established in the state, and likely to increase in the future.

What about Climate Change?

Climate change is also a huge driver of new invasive species introduction and spread. However, there still is much uncertainty surrounding the magnitude of this issue and its influence on the state’s resources. With increasing temperatures and a longer growing season, sea level rise, marsh migration, and other stressors related to climate change, it is difficult to predict what will come next. Invasive species can exploit climate change induced impacts in many ways. Some include:

- Range extension (e.g., cover a larger geographical area or move to new, favorable ones)

- Increased ability to over winter

- Greater success due to loss of a competitors (e.g., habitat no longer suitable due to higher temperatures, change in vegetation, change in prey, etc.)

- Higher viability of reproduction products (e.g., seeds, tubers, eggs, etc.)

To address these uncertainties, the NJDEP developed a comprehensive report that explores this phenomenon and related impacts: 2020 New Jersey Scientific Report on Climate Change. To learn more about climate change and how New Jersey is preparing, please see the following resources:

Preventing an invasive species from becoming established in the state is key. Knowing the life cycle of an invasion also helps with knowing what the right measures to take are. Once invasive species are introduced, there can be a time-lag during which the new population remains small and undetectable. However, over time (months, years, etc.) if not detected and no action is taken, the population can grow making management more costly and difficult.

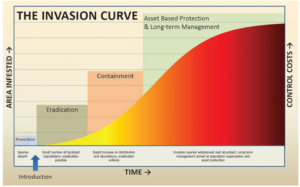

The invasion curve below shows how the life cycle of an invasion works. Essentially, as time increases, so does the invader’s population and costs for controlling. Once a species becomes widespread (many populations located throughout the state), eradication efforts are no longer effective. Local management of high value, priority areas then becomes the most important focus.

Mitigating the impacts caused by invasive species can be complicated. It can also be expensive and not always successful. However, education and public outreach are important tools for encouraging responsible environmental stewardship. Prevention of new invasive species invasions is key, though early detection/rapid response (ED/RR) are also effective. Management requires persistent application of adaptive methods and constrained by available resources.

Knowing what to look for is the first step in preventing and controlling the spread of invasive species to new locations. As a homeowner, you can remove invasive plants or treat pests that you encounter in your yard. You can also choose native plants or safe/sterile cultivars that will not escape from your chosen planting location. A list of safe plants for New Jersey can be found here: NJISST Do Not Plant List. Other resources for managing invasive species can be found on this page under How can I help? and Additional Resources.

The DEP has been actively involved with several projects to manage invasive species. The State also works with a diverse group external experts and stakeholders. Following recommendations provided in the 2009 NJ Strategic Management Plan for Invasive Species (2009 NJSMPIS) and drawing from state-derived and federal resources (see Additional Resources), DEP has and is currently implementing a number of prescribed management actions, which includes several ongoing projects. New Jersey’s Wildlife Action Plan (NJDEP| Fish & Wildlife | New Jersey’s State Wildlife Action Plan) also identifies several actions that can be implemented to improve habitat and protect the State’s biodiversity. Although these projects and recommended actions vary across programs, major areas of focus include:

- Protecting ash trees against the emerald ash borer

- Monitoring forests for pests including gypsy moths

- Restoring hemlock trees affected by hemlock woody adelgid infestations, habitat restoration, and breeding projects

- Small-scale management projects (invasive plant removal in parks, removal of spotted lanternfly egg masses, and aquatic invasive management)

- Controlling invasive species in highly sensitive areas (e.g., wood turtle habitat, bog turtle habitat, spreading globeflower habitat, northern metalmark butterfly habitat, vernal ponds, and calcareous sinkhole habitat), and

- Preventing the spread of invasive species while conducting field work

- Investigating presence/absence of invasive species through eDNA collection and molecular detection

These focus areas employ several management approaches to ensure success of projects. Examples include monitoring and outreach, habitat modification, herbicide application, mechanical removal of invasive plants, designing projects to favor native species establishment, ED/RR, monitoring and destroying invasive aquatic species, conducting surveys to document invasive populations, and seed banking for select at-risk forest species.

-

Clinging Jellyfish season underway in NJ back bays (June 2024)

-

USDA asks public to look out for Spotted Lantern Fly egg masses (March 2024)

-

NJ pushes for native plant comeback to combat invasive species (February 2024)

-

NJ Department of Agriculture proposes treating state lands for LDD (Gypsy moth) (January 2024)

-

NJ Department of Agriculture announces funding available (2024-26) to all NJ counties and municipalities for Spotted Lanternfly treatment (January 2024)

-

Proposed Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan public comment period is now closed

-

Lawmakers advance bill to ban invasive plants, revive statewide invasive species council– New Jersey Monitor (December 2022)

-

Invasive Species Removal Project Initiated in the Swartswood Natural Area– NJDEP Office of Natural Lands Management (2022)

Invasive Plants

Invasive Animals and Pests

Invasive Pathogens and Fungi

How can I help?

Strategic Management Plan

Aquatic Invasive Species Management Plan

Additional Resources

Contact Us

Last updated: June 19, 2024