In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

White Tailed Deer

Background

New Jersey’s white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) herd is a major component of the landscape throughout all areas of the state. “White-tailed” refers to the white underside of the tail, which is held conspicuously erect like a flag when the animal is alarmed or running. The adult white-tailed deer has a bright, reddish-brown summer coat and a duller, grayish-brown winter coat. White fur is located in a band behind the nose, in circles around the eyes, inside the ears, over the chin and throat, on the upper insides of the legs, and beneath the tail. The young, called fawns, have reddish coats with white spots.1

In the early 1900s, few deer remained in the state following unregulated hunting pressure, such as from the fur trade. The population rebounded in the mid to late 1900s, due to successful conservation measures as well as a reduction of many natural deer predators from New Jersey. Deer affect our forests, farms, gardens, backyards, health, and roadways. Today, many parts of New Jersey have overabundant deer populations that require management. Deer abundance is managed through regulated hunting. Hunting regulations vary spatially based on deer abundance and land use. The goal is to maintain a healthy deer population in New Jersey using licensed hunters to achieve tolerable densities.

Deer are photographed, watched, and hunted by many New Jersey residents and visitors. In New Jersey, hunters spend more than 100 million dollars each year2, which benefits a wide variety of New Jersey businesses. In 2022, 5% of the Middle Atlantic Division’s population (NY, NJ, and PA) participated in hunting activities, when the estimated nationwide average for annual hunting-related expenditures exceeded three thousand dollars per participant.3 Hunters surveyed in New Jersey spent about $650 on average hunting deer in the 2019-2020 season.4

Overabundant deer populations can have negative impacts on humans, as well as on the local ecology. Notable impacts to humans include vehicle collisions, depredation of agricultural and ornamental plantings, and the propagation of tick populations which carry infectious diseases (e.g., Lymes disease). Deer are often described as an “ecosystem engineer” species that can affect the ecosystem at many levels.5 Deer are selective browsers; over time, herds can extirpate (completely remove locally) some plant species and reduce the populations of others. Deer can also introduce and support the spread of invasive plant species. Native species often are the preferred food choice for deer, which consequently provides an advantage to invasive species’ establishment. In addition, because tree seedlings are shorter in height and especially vulnerable to deer, the future species composition of forests can be determined by deer browsing. While trees eventually grow out of a deer’s reach, many other plants never do. Browsing pressure from deer can significantly change habitat composition, which can affect numerous other species by altering the availability of resources like food and cover. When deer populations are overabundant, there is also increased deer-vs-deer competition for resources that can degrade the fitness of each individual.6

Deer populations may have the potential to impact forest regeneration, a major concern related to biodiversity. Recent research in New Jersey has shown significant decreases in seedlings, saplings, and trees compared with mid-20th century records, with evidence suggesting this was likely caused, in part, by increased deer populations.7 Studies in Pennsylvania involving enclosed areas have revealed a loss in animal and plant diversity as deer populations exceeded 10 per square mile. The depletion increased in a nearly linear fashion as deer density increased.8,9,10,11Another recent New Jersey study intensively managed deer densities below 10 per square mile over a twelve-year period through culling, hunting, and use of exclosure fencing. Recovery of forest understory and tree regeneration was documented in an ecologically degraded forest, with significant increases of both native and introduced plant species.12 While it is clear that over-browsing by deer does inhibit the growth of some tree species, many other factors affect forest regeneration. Therefore, blanket assumptions about what is a desirable density of deer should not be made, as this is site dependent and relates to ecosystem health. These studies are complicated by a variety of factors, including soil types, prior land use, slope, and canopy cover.

Status and Trends

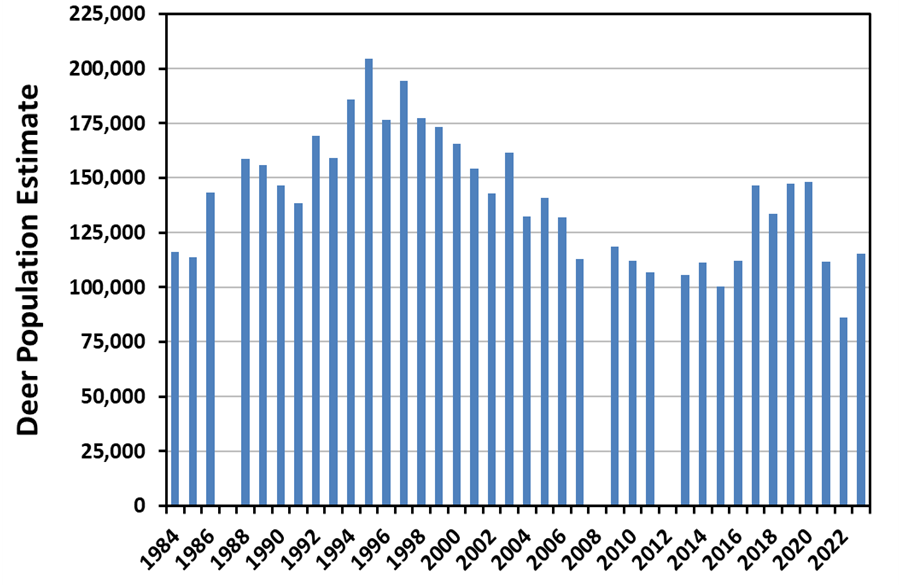

Figure 1 below shows the estimated summer deer population for 1984-2023. These estimates are derived by applying a standard reconstruction model to the hunter harvest data from the previous season. Although the trend appears to be generally decreasing since the mid-1990s, there are at least two factors which make it difficult to accurately determine statewide populations. First, changes in hunting regulations over the years introduce variability into the population estimates since the basic data is derived from hunter-harvested deer whose hunting behavior is affected by the regulations. Second, estimates for populations in non-hunted areas are not available, and this lack of information makes the population estimates conservatively low. Despite these data limitations, there was a notable decrease in the population estimates in 2021 and again in 2022. This drop may be attributable to a high harvest during the 2020-21 deer season resulting from a nationwide increase in hunter participation at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many hunters had more time to hunt. Additionally, New Jersey had back-to-back outbreaks of Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) in 2021 and 2022 which caused significant localized deer mortality.

Deer population densities also vary geographically in the state. Many suburban neighborhoods provide suitable habitat for deer but do not perform deer management, leading to locally elevated densities. If deer were evenly distributed throughout the state, which they are not, the 2023 population would average about 13 deer per square mile. Mercer County Park Commission estimated the Hopewell Valley region’s deer population in 2021 as 109 per square mile prior to birthing fawns.13 On the other hand, recent NJDEP Fish & Wildlife surveys estimated populations in the Pine Barrens portions of Cumberland and Atlantic Counties to be around 6 deer per square mile.14

Figure 1: New Jersey estimated deer population from 1984 to 2023. Estimates are not available for 1987, 2008, or 2012.

Outlook and Implications

Deer populations have reached problematic numbers in numerous areas of the state. In an effort to help reduce these populations, the NJDEP Fish & Wildlife has lengthened hunting seasons, increased harvest quotas (i.e., “bag limits”), increased hunting permit issuance, and offered incentives for hunters to harvest more does (does are the principal drivers of population growth). Development patterns, private landowner objections to hunting, and local regulations or ordinances that severely restrict or preclude hunting create substantial limitations to population management efforts. Public open space with full hunter access typically has much lower deer densities than surrounding areas where hunting is not allowed or is restricted. Although New Jersey has some of the most liberal deer hunting regulations in the nation, restricted hunter access results in undesirable deer densities in many areas of the state. In areas where recreational hunting is not considered to be a practical management tool, New Jersey has permitted alternative methods of controlling deer populations under the Community-Based Deer Management Permit program.15 These alternative methods may include controlled hunting, shooting by authorized agents, capture and euthanasia, and fertility control. There is also a “Deer Management Assistance Permit” (DMAP) allowing landowners or property managers to remove additional antlerless deer in areas with more restrictive regulations. Farmers also get free permits to hunt their properties and free depredation permits which allow for the taking of deer out of season to mitigate agricultural damage.

More Information

https://njdepwptest.net/njfw/hunting/deer-seasons-and-regulations/, NJDEP Fish and Wildlife

www.nhptv.org/natureworks/whitetaileddeer.htm, a public television site

https://njaes.rutgers.edu/fs1202/, NJ Agricultural Experiment Station

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Wildlife Populations: White-tailed Deer.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified January 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/white-tailed-deer.

Download the Data

The data used for Figure 1 are available to download here.

References

Much of the information in this report was provided by the NJDEP Fish and Wildlife website at https://njdepwptest.net/njfw/wildlife/white-tailed-deer/

1www.desertusa.com/mag99/june/papr/wtdeer.html, accessed online on 1/23/2025.

2U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Census Bureau, 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation- New Jersey. Revised December 2013. Accessed online on 1/23/2025 at:https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/fhw11-nat.pdf

3U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2022 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation. Accessed online on 1/23/2025 at: https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Final_2022-National-Survey_101223-accessible-single-page.pdf

4NJDEP Division of Fish and Wildlife, 2020, unpublished Hunter Harvest Survey data.

5Baiser, B., J. Lockwood, D. LaPuma, and M. Aronson, 2008, A perfect storm: two ecosystem engineers interact to degrade deciduous forests of New Jersey, Biol Invasions, 10, 785-795.

6Eschtruth, A.K., and J.J. Battles. 2009. Assessing the relative importance of disturbance, herbivory, diversity, and propagule pressure in exotic plant invasion. Ecological Monographs 79, 265–280.

7Kelly, J.F., 2019, Regional changes to forest understories since the mid-Twentieth Century: Effects of overabundant deer and other factors in northern New Jersey, Forest Ecology and Management, 444, 151-162.

8Katz, Larry, 2004, Rutgers University, personal communication.

9Tilghman, Nancy, 1989, Impacts of white-tailed deer on forest regeneration in Northwestern Pennsylvania, Journal of Wildlife Management, 53, 524-532.

10DeCalesta, David, 1994, Effects of white-tailed deer on songbirds within managed forests in Pennsylvania, Journal of Wildlife Management, 58, 711.

11U.S. Forest Service. Catalog #50: Effect of Deer Population Levels on Natural Regeneration of Allegheny Hardwoods. Accessed online on 1/23/2025 at: https://www.fs.usda.gov/ne/global/ltedb/catalogs/cat50.html

12Almendinger, T., Van Clef, M., Kelly, J.F., Allen, M.C. and Barreca, C., 2020, Restoring forests in central New Jersey through effective deer management, Ecological restoration, 38(4), 246-256

13Mercer County Park Commission, 2024, Deer Management Report, February 2024, https://www.mercercounty.org/home/showpublisheddocument/29695

14NJDEP Division of Fish and Wildlife, 2024, unpublished Spotlight Survey data.

15NJDEP Division of Fish and Wildlife, Community-Based Deer Management. Accessed 1/23/2025 at: http://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/cbdmp.htm