In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Horseshoe Crab

Background

Horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) are both ecologically and commercially important. They are particularly important in New Jersey because the Delaware Bay is the center of horseshoe crab spawning on the Atlantic coast,1 supporting the largest population in the world.2 Horseshoe crabs lay their eggs on sandy beaches in spring and summer, primarily during new and full moon cycles. Migrating shorebirds rely heavily on their eggs to supply the energy required to complete their migration.

Horseshoe crabs molt numerous times as they grow from the larval stage, shedding their exoskeleton at least 16 or 17 times before reaching sexual maturity. They require nine to ten years to reach maturity, when they cease to molt, and may reach a maximum age of twenty years.3 Adult horseshoe crabs spend the winter months in water 20 to 60 feet deep on the continental shelf. Increased water temperature and daylight stimulate adult migration toward sandy beaches for spawning. Their peak migration in the Delaware Bay generally occurs during the evening new and full moon tides in May and June. Females dig a shallow hole, ranging from 5 to 30 centimeters deep, within the intertidal zone, the area between the high and low tide marks, and deposit their eggs in clumps while males fertilize the eggs. Adverse weather can negatively affect spawning by disrupting spawning sites, driving animals off the beach, diminishing the number of pairs able to spawn, or preventing them from coming to the beach at all.3

Harvesting of horseshoe crabs has been documented since the 16th century.4 However, by the 1870s, industrial agriculture applications for livestock feed and fertilizer resulted in reported average annual harvests of more than one million crabs per year in the Delaware Bay for about five decades.5 By the 1960s, alternative sources of fertilizers were developed, which greatly reduced horseshoe crab harvesting.4

More recently, horseshoe crabs have been harvested commercially in some states for bait to catch American eels, catfish, and whelk. They are also caught for critical applications in the biomedical industry. However, following significant declines of shorebird species that depend on horseshoe crab eggs, New Jersey adopted a moratorium on the harvesting of horseshoe crabs in 2008 (N.J.S.A. 23:2B-21), with an exception for the nonlethal collection of blood from horseshoe crabs for biomedical purposes. Since 1970, biomedical companies have used wild caught horseshoe crabs for their blood, from which they produce Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL).6 LAL is used to detect contamination of injectable drugs and implantable devices; since it’s discovery it has been the most sensitive means available for detecting endotoxins, which are part of the outer membrane of the cell wall of certain bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella. Notably, there are now some synthetic alternatives to LAL, such as recombinant Factor C (rFC), that show comparable results for applications in the biomedical industry.6,7,8 In May 2025, the United States Pharmacopeia, a nonprofit organization that develops medical industry standards recognized by regulatory agencies, published methods for bacterial endotoxin testing using synthetic alternatives to LAL. Laboratories may continue testing with LAL but will now be able to begin the validation process for synthetic alternatives. If enough evidence is produced to demonstrate these alternatives are comparable to LAL testing methods, it is possible there will be broader applications of synthetic alternatives to LAL in the industry. If a synthetic product were adopted broadly, there is potential to reduce harvest and mortality rates of horseshoe crabs throughout their distribution.

Horseshoe crabs are managed under Addendum IX of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) Fishery Management Plan for Horseshoe Crab.9 A 2024 stock assessment update evaluated the status of several regional populations, including the Delaware Bay (New Jersey – Virginia) region.10 High harvest levels during the 1990s led to rapid population declines in the mid-Atlantic region. Management actions taken in 2004 and 2006 halted the population decline, and a recent stock assessment update indicated that the Delaware Bay population of horseshoe crabs appears to be recovering, with a current status above the modeled reference point (see this report for more information).10

Spawning horseshoe crabs at night (photo by NJDEP Fish & Wildlife)

Status and Trends

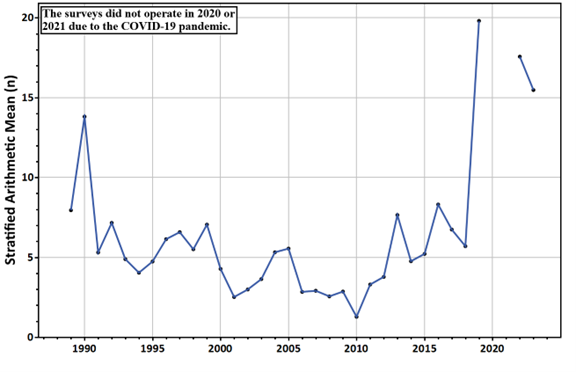

Within the Delaware Bay region, there are a number of surveys that provide information on population status. Although variability exists among the surveys, common trends are evident. In particular, longer time series indicate a rapid decline in abundance during the 1990s followed by apparent stability.9 Results of the New Jersey Ocean Trawl Survey show a significantly decreasing trend from 1988 to 2010 (Kendall’s tau = -0.55, p<0.05) and a significant increasing trend from 2011 to 2023 (Kendall’s tau = 0.64, p<0.05) (Figure 1).11 The surveys did not operate in 2020 or 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: New Jersey Ocean Trawl Survey stratified arithmetic mean catch per unit effort of horseshoe crabs for combined April, August and October samples (1989 to 2023).11 The stratified mean is derived by calculating the means for each stratum within the sampling area, multiplying each individual stratum mean by its stratum weight (percentage of area the stratum occupies within the entire sample area), then summing the weighted strata means.

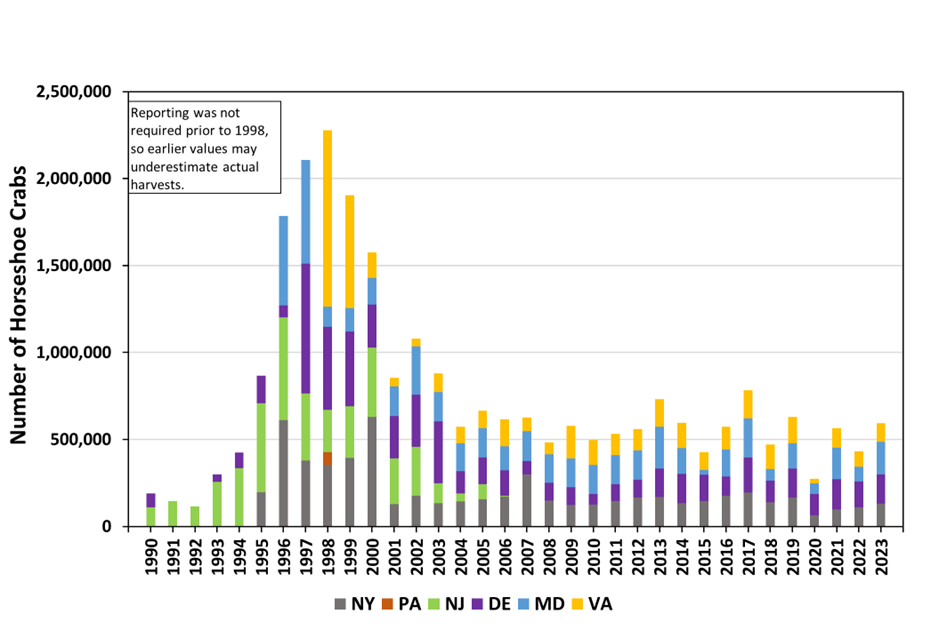

Harvest restrictions implemented in 2004 and 2006 have significantly reduced horseshoe crab harvest both coastwide and in the Delaware Bay region relative to the peak harvests in the late 1990s (see Figure 2), with a moratorium on bait harvest in New Jersey that went into effect in 2008. Despite an earlier lack of response to these management efforts, this region’s horseshoe crab population appears to be recovering. Yet there are other factors (e.g., bycatch, illegal harvest, environmental trends, ecosystem interactions), which have been difficult to quantify and account for in management of this species. For example, large bait harvests of the 1990’s focused primarily on breeding-age crabs, particularly females which are favored for bait.9 Population recovery following these large harvests was expected to be slow as horseshoe crabs are thought to take 10 years to reach spawning age.

Although horseshoe crabs may no longer be harvested for bait in New Jersey, there is a biomedical company authorized to capture horseshoe crabs, extract a quantity of blood for the production of LAL, then release the crabs. There is some mortality associated with this practice and the stock assessment modeling efforts take this into account when assessing mortality impacts to the population.10 Figure 2 shows the number of horseshoe crabs that are harvested coastwide for bait and biomedical purposes.10 Reduced food availability may also be affecting population recovery. For instance, there has been a significant decrease in surf clam (Spissula solidissima) populations, a major prey item of horseshoe crabs, in the mid-Atlantic region over the last two decades.12 Another factor that may be inhibiting population growth is loss of habitat, particularly spawning beaches in the Delaware Bay. Both New Jersey and Delaware are taking steps to protect and enhance bayshore beaches to ensure suitable spawning habitat.

Figure 2: Total number of horseshoe crabs harvested annually in the mid-Atlantic states (1990 to 2023).10,11

Outlook and Implications

Management efforts by the states and ASMFC has led to a decrease in commercial bait landings of horseshoe crabs from a coastwide average of 1.55 million per year from 1998-2003, peaking at over 2.6 million in 1999, to an average of 727,652 per year from 2004-2022, with a high of around 1 million crabs in 2017.10 The importance of horseshoe crabs to species such as the red knot requires that horseshoe crab abundance be sufficient to support not only the human use, but needs of other species as well. To achieve these goals, the ASMFC developed a multispecies management framework that includes horseshoe crabs and red knots.14 In 2013, the Adaptive Resource Management (or ARM) model was implemented, which identifies an optimum harvest strategy for the Delaware Bay region that considers the utility of crabs to both ecosystem dynamics and human use. The 2023 fishing year had a harvest recommendation of 475,000 male and 125,000 female horseshoe crabs. However, acknowledging the public’s concern about the status of the red knot population, the Management Board elected to have a quota of zero females and 475,000 males allocated among the states.

In addition to harvest restrictions, there have been substantial efforts since 2003 to reduce human disturbance on NJ Bayshore beaches. Restricting access to important nesting beaches on the Delaware Bay prevents the disturbance of breeding horseshoe crabs and feeding shorebirds. Since 2013, horseshoe crab spawning habitat restoration have been ongoing. With initial funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Community Foundation of NJ, and the Department of Interior, over one mile of spawning beach in Cape May and Cumberland Counties was restored after Hurricane Sandy (2013-2014). Since then, several sites in Cumberland and Cape May counties have undergone beach and salt marsh restoration efforts to support horseshoe crab spawning habitat, including at Dyers Cove, Cooks Beach, Thompsons Beach, Fortescue, Reeds Beach, Kimble Beach, Moores Beach, Dyers Cove, and Pierces Point. These efforts include experimental projects conducted by the American Littoral Society (ALS), involving the removal of rubble on beaches, adding large quantities of sand for beach replenishment, and increasing elevation/revegetation of marsh damaged by salt hay farming.15,16 ALS reports their restoration projects have been implemented at over 6.5 miles of shoreline between 2013 and 2022. Continued restoration efforts are expected to increase populations of horseshoe crabs and red knots.

Because of the importance of horseshoe crab eggs as a primary food source for several species of migratory shorebirds, especially red knots, studies of horseshoe crab egg density have been performed periodically in New Jersey since 1985. These data have demonstrated a dramatic decline in horseshoe crab egg density over time, which corresponds with the period of intense harvest during the mid-1990s and early 2000s. Egg abundance data were used to estimate an average of 156,600 eggs per square meter (eggs/m2) from 1985-1987,17 49,782 eggs/m2 from 1990 and 1991,18 and 4,621 eggs/m2 in 1999.19 Since the height of horseshoe crab harvesting, recovery of egg abundances has been slow. Estimates from 2015-2021 sampling efforts averaged 10,243 eggs/m2, which is more than 10 times below the estimates from the 1980s.17 Egg surveys conducted in Delaware and New Jersey found essentially no change in egg density from 2005 through 2014.20 On New Jersey beaches only, egg density in the top five centimeters of sand have not shown substantial increases over the period 2000-2019.21 Notably, Mispillion Harbor, DE, continues to be an important shorebird foraging area with very high egg densities. The harbor is protected in all weather conditions and may enjoy earlier, warmer water temperatures; both aspects favor horseshoe crab spawning.

Given the life history of horseshoe crabs, population growth will be slow and may be hindered by factors such as continued human use, habitat loss, food availability, illegal harvest, and incidental mortality; however, NJDEP is taking steps, such as a harvest moratorium and beach replenishment, to protect this keystone species for the maximum benefit of all users.

Adult horseshoe crab in Cape May, NJ (photo by NJDEP staff)

More Information

For more information on horseshoe crabs, visit the following resources:

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission webpage, click “Species”, then select “Horseshoe Crab.”

- United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) species page on Atlantic Horseshoe Crabs

More information on red knots is available in “Wildlife Populations: Red Knot” in the NJDEP Environmental Trends series at https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends

Errata from the 2020 Report

The NJ Ocean Trawl is a stock assessment survey focused on oceanic species off the NJ coast, including horseshoe crabs. The trawling survey events occur annually during the months of January, April, June, August, and October. Notably, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) and NJFW have determined that catch per unit effort, calculated from survey data and used to assess horseshoe crab stocks, should not include sampling events during times when horseshoe crabs are not expected to be present. Thus, the data in Figure 1 reports the stratified arithmetic mean catch per unit effort, excluding 2 of the 5 months when samples are collected. Specifically, January is excluded when crabs are elsewhere, and June is excluded when crabs are breeding on shore. This selection is done to avoid inclusion of misrepresentative zero catch sampling events that would pull down the average catch rate. However, the previous horseshoe crab Environmental Trends Report from 2020 inadvertently included all 5 months of sampling in the figure and inaccurately described it as the stratified arithmetic mean catch per unit effort from April, August, and October. In this update, this has been corrected to only include the data from April, August, and October, thereby notably increasing the average catch per unit effort.

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Wildlife Populations: Horseshoe Crab.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified May 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/horseshoe-crab/.

Download the Data

The data used in Figures 1 and 2 is available to download here.

References

1Hata, D and J. Berkson. 2003. Abundance of horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus) in the Delaware Bay area. Fishery Bulletin 101:933-938.

2NOAA. Are horseshoe crabs really crabs? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/horseshoe-crab.html, 06/16/2024.

3Walls, E. A., J. Berkson, and S. A. Smith. 2002. The Horseshoe Crab, Limulus polyphemus: 200 Million Years of Existence, 100 Years of Study.

4Kreamer, G. and Michels, S., 2009. History of horseshoe crab harvest on Delaware Bay. Biology and conservation of horseshoe crabs, pp.299-313.

5Shuster, C.N. and Botton, M.L., 1985. A contribution to the population biology of horseshoe crabs, Limulus polyphemus (L.), in Delaware Bay. Estuaries, 8, pp.363-372.

6Maloney, T., Phelan, R. and Simmons, N., 2018. Saving the horseshoe crab: A synthetic alternative to horseshoe crab blood for endotoxin detection. PLoS biology, 16(10), p.e2006607.

7Bolden, J., Knutsen, C., Levin, J., Milne, C., Morris, T., Mozier, N., Spreitzer, I. and von Wintzingerode, F., 2020. Currently available recombinant alternatives to horseshoe crab blood lysates: Are they comparable for the detection of environmental bacterial endotoxins? A review. PDA Journal of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology, 74(5), pp.602-611.

8Kang, D.H., Yun, S.Y., Eum, S., Yoon, K.E., Ryu, S.R., Lee, C., Heo, H.R. and Lee, K.M., 2024. A Study on the Application of Recombinant Factor C (rFC) Assay Using Biopharmaceuticals. Microorganisms, 12(3), p.516.

9Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). 2025. Addendum IX to the Horseshoe Crab Fishery Management Plan. Arlington, VA. 13 pp.

10Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). 2024. 2024 Horseshoe Crab Stock Assessment Update. Arlington, VA. 92pp. https://asmfc.org/resources/science/stock-assessment/horseshoe-crab-stock-assessment-update-2024/

11New Jersey Ocean Trawl Survey data provided by Danielle Dyson, August 2024.

12Normant, J.C. 2015. Inventory of New Jersey’s surf clam Spisula solidissima resource.

13Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). 2024. Review of the Interstate Fishery Management Plan: Horseshoe Crab (Limulus polyphemus) 2023 Fishing Year. 31 pp. https://asmfc.org/resources/management/management-plan-review/horseshoe-crab-fmp-review-2023/

14Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC). 2009. A Framework for Adaptive Management of Horseshoe Crab harvest in the Delaware Bay Constrained by Red Knot Conservation. Stock assessment report no 09-02 (Supplement B) of the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. 46 pp. https://asmfc.org/resources/science/stock-assessment/a-framework-for-adaptive-management-of-horseshoe-crab-harvest-in-the-delaware-bay-constrained-by-red-knot-conservation-2009/

15Smith, J. A. M., S. F. Hafner, and L. J. Niles. 2017. The impact of past management practices on tidal marsh resilience to sea level rise in the Delaware Estuary. Ocean & Coastal Management 149:33-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.09.010

16Smith, J. A. M., L. J. Niles, S. F. Hafner, A. Modjeski, and T. Dillingham, 2020. Beach restoration improves habitat quality for American horseshoe crabs and shorebirds in the Delaware Bay, USA. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 645:91-107. https://www.smithjam.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Smith-et-al-2020-Delaware-Bay-beach-restoration.pdf

17Smith, J.A., Dey, A., Williams, K., Diehl, T., Feigin, S. and Niles, L.J., 2022. Horseshoe crab egg availability for shorebirds in Delaware Bay: Dramatic reduction after unregulated horseshoe crab harvest and limited recovery after 20 years of management. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 32(12), pp.1913-1925.

18Botton, M.L., Loveland, R.E. and Jacobsen, T.R., 1994. Site selection by migratory shorebirds in Delaware Bay, and its relationship to beach characteristics and abundance of horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus) eggs. The Auk, 111(3), pp.605-616.

19Pooler, P.S., Smith, D.R., Loveland, R.E., Botton, M.L. and Michels, S.F., 2003. Assessment of sampling methods to estimate horseshoe crab (Limulus polyphemus L.) egg density in Delaware Bay.

20Dey, A. D., M. Danihel, L. Niles, K. Kalasz, G. Morrision, B. Watts, H. Sitters. 2014. Update to the status of the red knot (Calidris canutus rufa) in the Western Hemisphere, August 2014. Draft Report 9‐5‐14, 11 pages.

21Dey, A. D., L. Niles, J. Smith, H. Sitters, and G. Morrision. 2020. Update to the status of the red knot (Calidris canutus rufa) in the Western Hemisphere, March 2020. 29 pages. https://njdepwptest.net/njfw/wp-content/uploads/njfw/redknotupdate-Final-3-3-20.pdf