Why do we need to age fish? What you may not know is ageing a sub sample of fish captured will give coastal fisheries scientists vital information about species growth rates, age at maturity, and year class information. This data can then be used in age-based stock assessments to determine natural and fishing mortality, to follow cohorts through time, and determine longevity of a species. These values can differ amongst locations and thus the more data we can collect the more accurate our estimates can be.

Now you might be asking yourself, how do you age a fish?

It’s a fascintaing process, but before we get into that, let’s talk about the species we age here at the Nacote Creek Research Station and how we get our samples.

Our biologists collect age structures from a variety of species, including American eel (Anguilla rostrata), Atlantic croaker (Micropogonias undulatus), striped bass (Morone saxatilis), tautog (Tautoga onitis), weakfish (Cynoscion regalis), summer flounder (Paralichthys detatus), black sea bass (Centropristis striata), bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix), Atlantic menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus), and winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus). Depending on the species and data needs, we will obtain our samples from a variety of sources including commercial fisheries, independent research surveys and recreational anglers.

In order to tell the age of a fish, we first need to collect bony structures that are used by fisheries scientists throughout the world. The preferred structure used in aging a fish is the otolith, but fin spines, opercula, and/or scales can be collected to age select species as well. Any structure that is used for ageing along the Atlantic coast has gone through a validation process to confirm the structure is accurate for ageing.

THE OTOLITHS

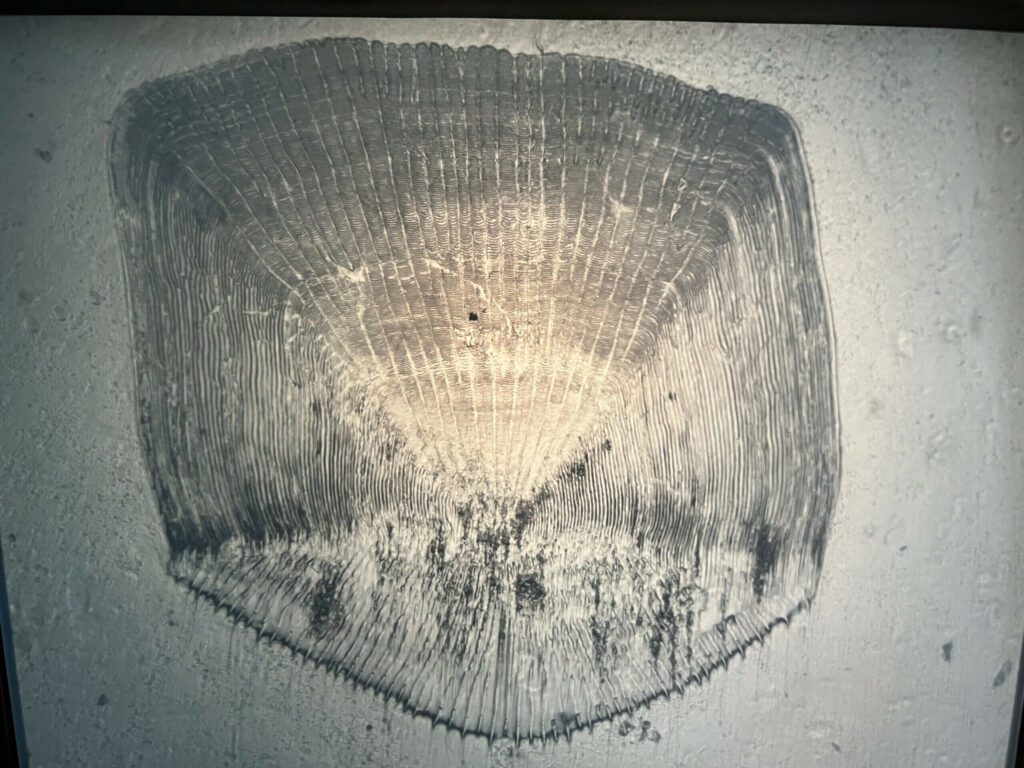

Otoliths, also known as ear stones, are hard calcium carbonate structures located behind the brain of bony fish. There are 3 pairs of otoliths (sagitta, asteriscus, lapillus), and they aid in balance and hearing. The otoliths grow inside the fish by layers of calcium building on top of one another throughout the life of the fish. Depending on the season of the year, the fish experiences slow growth and fast growth periods. When the fish is in a slow growth period the otoliths develop an opaque zone, and during fast growth they develop a translucent zone. A slow growth and fast growth area of the otolith is considered one year of age. These areas in the otolith are known as annuli. Biologists generally use the sagitta to age because they are the largest of the ear bones and the easiest to distinguish each annulus. Each species of fish has a unique otolith size and shape. American eels have very small otoliths, while weakfish and Atlantic croaker have rather large ones. The otoliths are extracted from the fish and stored in either vials or paper envelopes for drying. There are two potential ways we will age using the otoliths, whole and sectioned. If the otolith is determined to be sectioned, we will mark the nucleus (or core) of the otoliths, an essential process to ensure sectioning the center of the otolith. By sectioning the center, we will expose every annulus that has formed since the birth of the fish. We will then mount it to a small paper tag to fit in the jig of our saw. Once marked and mounted, we set up our low speed saw with a two or four blade set up to cut thin cross-sections from the otolith. Once we have our cross-sections, they are mounted on a microscope slide with a clear resin. After they are mounted on the slide, they will be inspected and if deemed necessary they can be polished, otherwise they will be stored for ageing.

THE SPINES

Fin spines, as their name suggests, are found in the fins of some bony fish. This structure is relatively new to the ageing scene, but it’s gaining popularity among biologists. The spines are a nonlethal structure that would allow scientists to gain the age of the fish, without sacrificing the fish. Processing a fin spine is similar to processing an otolith. They are first embedded in epoxy, then mounted to the paper tag and sectioned with the four-blade setup in our low speed saw to obtain 3 thin cross-sections. These cross-sections are then mounted on a microscope slide and stored for ageing.

THE SCALES

Scales have long been used for the ageing of fish. You might have participated in a tournament where we may have asked to acquire a scale sample from your Striped Bass before! When a fish ages, rings form on the scales similar to the other boney structures we have talked about so far. These rings are also known as annuli and scientists will attempt to count the annuli on a scale to determine the age of the fish. The key to ageing scales is obtaining scales that have not been regenerated. Like hair on our heads, when scales fall off a fish they can and will regrow, but that regrown scale will have scarring. That scarring will make it impossible to age, thus we try to take numerous scales to obtain a non-regenerated scale. Once a sample is obtained it will be stored and dried in paper envelopes. When the scales have dried, we have a few methods for preparing the scales for ageing.

Smaller scales can be aged directly on a magnifier called a Microfiche. Other scales, such as Atlantic Menhaden scales will be pressed together between two glass slides before being viewed under the Microfiche for ageing. The final way we prepare scales (especially larger scales) is by making a scale impression on an acetate slide by using a heated hydraulic press. This will ensure longevity of the sample, because larger scales tend to curl and get brittle in time.

THE OPERCULA

Opercula (operculum singular) are hard, bony plate like structures that protect the gills of bony fish. They are one of the most common ways to age tautog because their otoliths are extremely small. To extract the opercula from the fish we must cut the bone out of the fish. Once the bone is extracted it needs to be cleaned of all the flesh that is attached. To do this, we boil the bony structure and use a tooth brush to gently remove the flesh. Once we have the clean operculum, it is ready to be aged.

Additional Information on Ageing

Ageing Lab Coordinator

Jamie Darrow, Fisheries Biologist

Jamie.Darrow@dep.nj.gov

609-748-2020

Official Site of The State of New Jersey

Official Site of The State of New Jersey