Public Reminded to Follow Guidelines for Bats in Buildings

Bats are a fascinating, adaptable, and widespread group of animals, not to mention one of the most beneficial to people. Bats make up nearly a quarter of all mammals on earth, both in species diversity and sheer numbers. New Jersey is home to nine different species of bats, and whether you live on a farm, in the forest, along the shore or in a city, bats are most certainly close by.

Bats Through the Seasons

During the warm months, bats roost by day in narrow nooks and crevices where other animals won’t see or can’t reach. Many live inside tree cavities, beneath loose bark, or tucked behind shutters or in the attic of a house. Red bats (Lasiurus borealis) and Hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus) roost in the canopy of trees and shrubs, just dangling among the leaves for camouflage. Eastern small-footed bats (Myotis leibii) roost mainly in rock crevices within talus slopes and cliffs.

Female bats often group into large colonies in the spring and summer to share safe, warm spaces where they can raise their pups. These “maternity colonies” can number in the tens or hundreds of bats, though it’s rare to find those really large colonies since the arrival of White-nose Syndrome. Most mother bats give birth to just one pup each spring, in May or June, and nurse for about a month until that pup can fly and feed on its own. A bat colony will use the same familiar roosts year after year.

Bats are active outside the roost at night, of course. Stare overhead for a while at dusk and there’s a good chance you’ll see one, flapping and swooping through the sky. They spend the night foraging on insects – consuming at least half their own body weight worth of bugs each night and twice that amount when they’re pregnant or nursing (that’s equivalent to more than 3,000 mosquito-sized insects per night). A study published in Science magazine estimates the value of bats’ insect-eating services at between $3.7 billion and $53 billion per year to U.S. agriculture by preventing crop damage and reducing the need for pesticides (Boyle et al. 2011). Bats navigate the night skies by echolocation, where their high-frequency vocalizations bounce off objects around them and return to their ears as echoes.

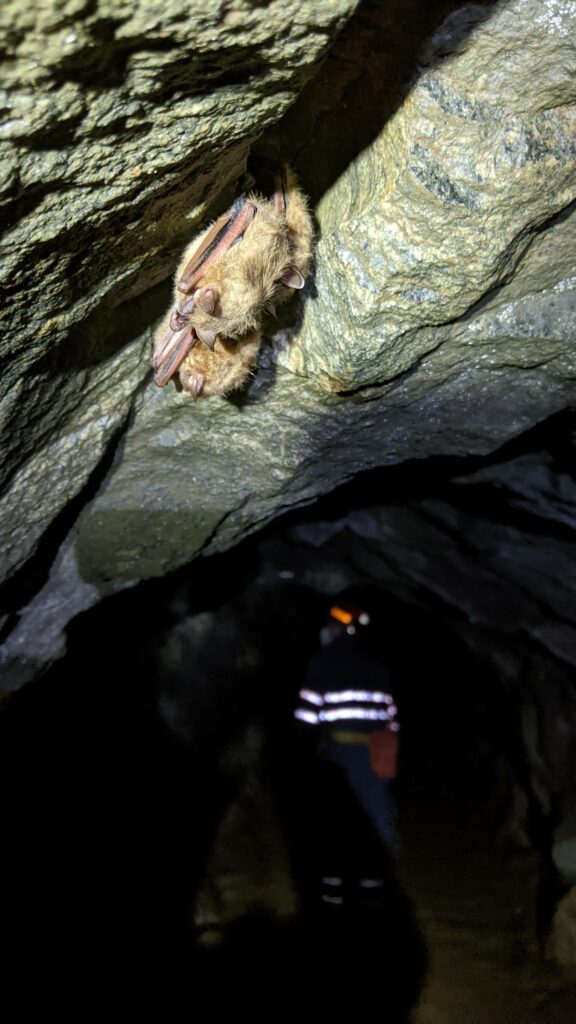

As winter approaches, temperatures drop and insects dwindle. A few NJ bat species migrate farther south to warmer climates, but most stay relatively “local” and hibernate. Many former mines, natural caves, and abandoned railroad tunnels offer the right above-freezing temperatures, humidity and solitude that bats require to overwinter below ground. A significant drop in heart rate, metabolism, and body temperature allow bats to conserve energy and survive for several months without food until spring returns.

Bat Projects in NJ

NJFW’s Endangered and Nongame Species Program has a variety of ongoing projects to monitor, conserve and better understand our state’s bat community. NJFW is part of the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat), which centers on long-term population monitoring. One element of our NABat project is statewide acoustic surveillance, wherein acoustic bat detectors are used to record the high-frequency echolocation calls of bats overhead at 24 point locations and along 12 driving transects each summer. Since different bat species have unique call patterns, acoustic detection is a great tool for documenting the abundance and diversity of bats in an area pretty easily, and without disturbing them. Capture-and-release of bats using mist-nets allows us to assess their health, reproductive success and other traits, as well as to appmly forearm bands (much like the leg bands used to identify birds) and even radio-track bats to their roosts using tiny transmitters. A newer generation of transmitters called ‘nanotags’ are now being used to study migratory bat flight pathways and the distances they travel, with the help of automated Motus telemetry receiver stations.

Winter hibernacula surveys are another important way to monitor bat populations over time, since bats from across the landscape gather together into relatively few known sites to hibernate. In the winter months, bats dot the walls and ceilings of caves and mines and can be counted in place, like a census. Bats are especially vulnerable to disturbance and vandalism during hibernation, so preserving lands that contain hibernacula and installing bat-friendly (people-proof) gates are key to conserving bat populations.

NJFW and countless others continue to track the effects of White-nose Syndrome (WNS), a disease caused by the exotic cold-loving fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd). The fungus invades bats’ skin in winter, when their immune response and other body functions are low. WNS has devastated bats, killing 90-100% in many affected sites. Tens of thousands of NJ bats and several million across the continent have died since its arrival to North America in 2006. In more optimistic news, Little brown bat survival rates have been improving in NJ (Maslo et. al 2015), and a Rutgers University-led study of Little brown bats from NJ, NY and VT found that WNS survivors have certain genes in common, pointing to a possible genetic resistance to the disease.

Volunteer Opportunity! New Jersey Fish and Wildlife’s 12 mobile acoustic transects are surveyed mostly by volunteers each summer. Volunteers adopt a driving route (about 10-30 miles long) to survey twice in June/July – after dark, of course – while acoustic equipment records the vocalizations of bats flying nearby. For more details and a map of the transect grids, visit the Conserve Wildlife Foundation’s page (here). Contact MacKenzie.Hall@dep.nj.gov to inquire.

More Information

- Need Help? Visit our Bats in Buildings page.

- Report bat sightings with NJ Wildlife Tracker! Must include a close enough photo that we can identify the species. Please do not disturb or touch any bats you find.

- Got Bats? Join the Summer Bat Count!

- Injured bat? Please contact a NJ Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitator who treats bats.

- Bat House Best Management Practices: brochure version (4 pages) or full document

- Build a bat house! Bat House Floor Plans

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Bats are one of the most important misunderstood animals

- The Creature Show’s bat episode gives a glimpse into the lives of bats, their struggle with White-nose Syndrome, and work being done in NJ to understand and conserve these animals.

Official Site of The State of New Jersey

Official Site of The State of New Jersey