In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Wildlife Populations: Wood Duck

Background

The wood duck (Aix sponsa) is one of many species of waterfowl that nest in North America.1 It is an important game species, comprising 7.5% of the annual waterfowl harvest in 2022 in the US.2 In the Atlantic Flyway, the wood duck is the most harvested waterfowl species, while in New Jersey other species are harvested in greater numbers, including the Canada Goose, Bufflehead, and Mallard.2 The wood duck is a small to medium-sized duck with a crested head, broad wings, and a large rectangular tail.3 The sexes are dimorphic with the male quite distinctive in its alternate (breeding) plumage and the female generally more drab (see Figure 1). Both males in eclipse (basic) plumage and juveniles resemble the more neutral females.

Male (breeding plumage)

- Iridescent green and purple head

- White throat with finger-like extensions onto the cheek

- Large red eyes

- Long green, purple, and white crest

- Burgundy breast

Female

- Brownish to gray

- White patch around the eyes

- White chest

- Gray crest

Figure 1. Descriptive characteristics of sexual dimorphism in wood ducks.3

The wood duck is a dabbling duck, which means it generally stays on the water surface and “tips up” for food items in shallow water; it is, however, a more efficient diver than other dabbling ducks and easily dives for corn or acorns in several feet of water.4 Wood ducks nest in natural cavities or in nest houses. They are smaller than mallard ducks and it is believed that their size may have evolved to exploit cavities created by pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), with which they share their breeding range.4

Unlike other dabbling ducks, wood ducks are adept at perching in trees and flying between tree branches.4 They are also skilled at walking on land and often seek food in uplands that are several miles from the nearest water.4 Because of these behaviors, wood ducks are at home in a wide variety of wetland habitats, and they are uniquely adapted to breed in the deciduous forest biome, even to the point of nesting in cities and towns.

Some of the adaptations that allow the wood duck to exploit these habitats are broad wings, large eyes, and a long tail.4 Out of all species of game duck, the wood duck has the broadest wing in proportion to its length; this increased wing size supports flight between the branches of trees.4 Wood ducks also have the largest eyes of any waterfowl; in addition to being advantageous at low light intensity, it allows greater acuity which further enables them to efficiently fly through branches.4 The wood duck also has a longer tail than almost all of the other dabbling ducks; this contributes to greater maneuverability during flight, resulting in less risk of injury when navigating through the large number of densely-packed trees in its habitat.4

Early ornithologists in North America reported robust populations of wood ducks until late in the nineteenth century, after which numbers began to decline, especially near large cities.4 This decline was likely the result of overharvest, deforestation, and loss of wetland habitats. By World War I, wood ducks were at extremely low levels over much of their range, as was the case with many other species of waterfowl.4 Because of this, a number of bills were passed nationally to address dwindling populations; these included the Weeks-McLean Bill (1913), which gave the federal government custody of migratory birds and prohibited the hunting of wood ducks; and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918), which resulted in a limit of one wood duck per hunter that lasted until 1941.4 The wood duck’s range, largely confined to areas populated by humans, made it vulnerable for longer periods of time than species that bred in more sparsely inhabited areas. Use of specially designed nest boxes, expanding beaver (Castor canadensis) populations which create favorable wetland habitat, regrowth of forested areas, and managed hunting seasons have all contributed to the recovery of the wood duck in North America.4

Today wood ducks are abundant throughout most of New Jersey. Highest densities are reached in forested and scrub-shrub wetlands adjacent to mature forests. The presence of abundant wood ducks in freshwater wetlands is indicative of healthy ecosystems.

Status and Trends

Due to the migratory nature of waterfowl, monitoring programs are conducted on a flyway or continental scale requiring the participation of numerous states, provincial, federal (US and Canadian), and non-government partners. New Jersey is a member of the Atlantic Flyway Council (AFC), which provides the means to participate in promulgating annual hunting regulations and long-term management plans in cooperation with partner states and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. NJDEP Fish & Wildlife (NJFW) works in a cooperative manner with the numerous government and non-government agencies responsible for the populations and habitats of migratory game birds.5

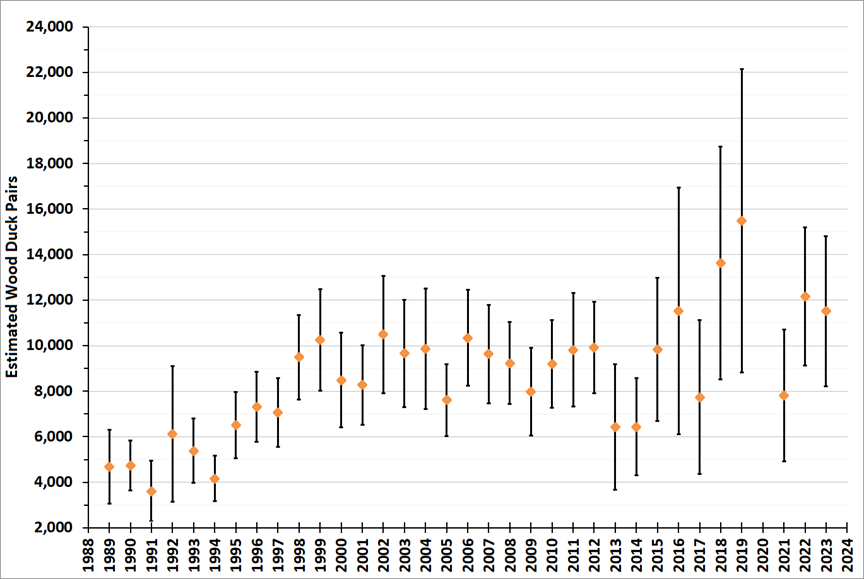

NJFW conducts the Atlantic Flyway Breeding Waterfowl Survey (AFBWS) each spring along with other AFC partners across 11 states. These ground surveys are conducted in randomly located, one kilometer plots by observers in boats, vehicles, and on foot. The AFBWS is designed to provide estimates for the entire Atlantic Flyway survey area, meaning that state level estimates are less precise. NJFW extrapolates the plot survey data to provide the best statewide estimates of the New Jersey population of wood duck breeding pairs (Figure 2).5 Notably, the number of plots surveyed was reduced from 250 to 105 sites in 2013, which explains the increased variability seen in subsequent estimates. No surveys were conducted in 2020 due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

From 1989 to 2023, the long-term annual average is estimated as 8,600 wood duck breeding pairs in New Jersey.5 The annual estimates show a fluctuating wood duck population of breeding pairs ranging from 3,609 in 1991 to 15,486 in 2019. Overall, the data shows a period of apparent increase from 1989 to 1999, then a relatively stable population through present.5 Notably, in 2013 and 2014 the estimated number of breeding pairs sharply decreased by more than 3,000 breeding pairs compared to the 2012 estimate.5 While the population estimates from year to year have shown greater variability since 2013, there appears to be a general increase in the number of breeding pairs over the last decade. In 2023, the estimated number of breeding pairs of wood ducks was roughly two and a half times higher than it was in 1989.5

Figure 2. Estimated number of breeding pairs of wood ducks in New Jersey during the spring. Atlantic Flyway Breeding Waterfowl Survey, 1989-2023. The error bars on each point are calculated by multiplying the coefficient of variation by the respective data value. Data from this figure can be accessed in the “Download the Data” section below.

Outlook and Implications

Despite the apparent fluctuation in breeding pairs in New Jersey, population indices from the Breeding Bird Survey, which is performed across a larger spatial scale encompassing the entire breeding range of the wood duck, indicates an increasing population in North America.6

More Information

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Wildlife Populations: Wood Ducks.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified April 2024. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/wood-duck/.

Download the data

The data used for Figure 2 are available to download here.

References

1Johnsguard, Paul A., “Waterfowl of North America: The Biology of Waterfowl” (2010), Waterfowl of North America, Revised Edition (2010).4. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciwaterfowlna/4 accessed 2/5/2024.

2Raftovich, R.V., S. C. Chandler, and K.K. Fleming. 2023. Migratory Bird Hunting Activity and Harvest for the 2021-22 and 2022-23 Hunting Seasons. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland, USA.

3National Audubon Society. “Guide to North American Birds”. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/wood-duck accessed on 2/5/2024.

4Bellrose, F.C. and D.J. Holm. Ecology and Management of the Wood Duck. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994.

5NJDEP, Division of Fish and Wildlife. “Waterfowl and Migratory Birds in New Jersey.” https://njdepwptest.net/njfw/hunting/waterfowl-and-migratory-birds-in-new-jersey/ accessed 2/5/2024

6Zimmerman, G.S., J.R. Sauer, G.S. Boomer, P.K. Devers, and P.R. Garrettson. (2017). Integrating Breeding Bird Survey and demographic data to estimate Wood Duck population size in the Atlantic Flyway. The Condor, 119, 616-628. https://doi.org/10.1650/CONDOR-17-7.1.