In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Long-legged Wading Birds

Background

Long-legged wading birds are prominent members of estuarine ecosystems. They are one of two groups of colonial-nesting waterbirds highlighted in New Jersey’s Environmental Trends Report series (see Seabirds report). Colonial-nesting waterbird is a collective term used to refer to a large number of species that share two common characteristics:

(1) They tend to nest in close proximity to one another during the breeding season.

(2) They gather most of their food from the water, mainly fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Colonial waterbirds have attracted the attention of scientists, conservationists, and the public, especially since the early 1900s when plume hunters nearly drove many species to extinction. Although the populations of many species rebounded in the middle part of the 20th century, major losses, diminished resources of prey fish resulting from overexploitation, and alteration of freshwater and coastal wetland habitats still threaten the long-term sustainability of many colonial waterbirds. Many of these species have not recovered from these impacts, including some that have been listed as threatened or endangered in the United States or in New Jersey.1 These birds are important predators, feeding near the top of the food chain. They serve as valuable indicators of environmental quality, including resource abundance and health; levels of toxic substances, such as organic contaminants and heavy metals; and levels of human disturbance.

Snowy Egrets (Egretta thula) and Black-crowned night herons (Nycticorax nycticorax) are particularly good indicators of estuarine systems because they both feed and nest in the Atlantic Coastal ecosystem and are prominent in New Jersey. The Snowy Egret can be distinguished from the Great Egret by its smaller size, its black bill, and yellow feet. The Snowy Egret can be spotted from spring through fall, often along the edge of the water in a marsh.

The Black-crowned night heron is a stocky heron with plumage that is black, gray, and white with a distinctive black cap and a pair of white plumes that extend from the back of the head. They nest colonially and nests can be anywhere from among reeds in marshes to 160 feet above the ground in trees. Their spring migration generally occurs from mid-February through mid-May. Fall migration occurs from mid-July through October. The Black-crowned night heron is widely distributed throughout North America, South America, Eurasia, and Africa.2

Survey Description

For nearly five decades, NJDEP Fish and Wildlife (NJFW) has monitored the nesting populations of colonial waterbirds through a combination of ground and aerial surveys.

Ground surveys are primarily conducted on non-marsh islands, where nesting areas are easier to access. This typically targets long-legged wading bird species that readily nest off of marsh islands. This includes inland areas and barrier islands, but are often in human-dominated landscapes, including residential properties, local parks, and similar areas. These surveys highlight the plasticity of some species and provide insights for bird conservation strategies if the marsh environment becomes less suitable for nesting in the future. Observers tally the number of adults, nests, and fledged chicks. Ground survey data are not included in the data trends and figures below, as it is not as consistently or comprehensively collected, and therefore not suitable for long-term trends analyses.

Aerial surveys have been conducted since 1976 and are used for the trends summarized below in this report. These surveys follow a protocol that entails counting all adult birds associated with a landmass in the marshes and back bay habitats from Mantoloking to Cape May by helicopter. Nesting by these species in other portions of the state are not included in this dataset. However, the majority of the nesting sites for these species are captured on this survey. The protocol is consistent and appropriate to establish long-term trends. The trends reported below are based on population indices, and should not be considered population estimates, which require much more intensive surveying efforts for a sufficient dataset and are notoriously difficult to obtain. The trends instead summarize population indices, which are a one-time count conducted each season. Notably, aerial surveys tend to underestimate the number of adults present, especially for those birds with dark plumage, which can be difficult to see through the cover of vegetation.

Status and Trends

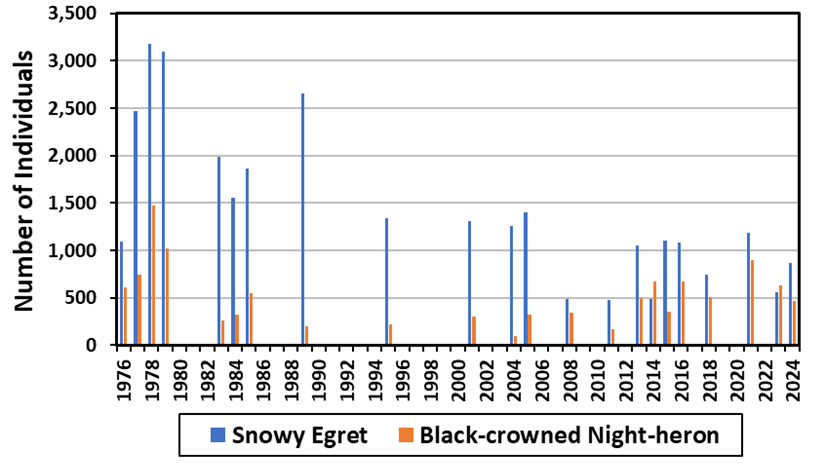

Long-term trends in Figure 1 reveal that the Snowy Egret population has significantly declined since monitoring efforts began in 1976 through 2024 (Kendall Tau Correlation, rho = -0.55, p <0.05). Since the late 1980s, the population indices from monitoring observations have been notably lower than the baseline, and this trend has continued through 2024. Observations of the Black-crowned night heron indicate they have also been declining since the 1970s: however, the population indices have shown a slight rebound since 2013.

Figure 1. Number of Snowy Egret and Black-crowned night heron individuals as counted from aerial surveys. Years without counts represent years when surveys were not conducted.

Outlook and Implications

The Black-crowned night heron is not federally listed as threatened or endangered: however, in 1999, the breeding population was added to the New Jersey list of threatened species at N.J.A.C. 7:25-4.17 and its status remains threatened. The same state ruling classifies the breeding population of Snowy Egrets as a species of special concern. Although the data suggest the number of adult Snowy Egrets and Black-crowned night herons tallied on the aerial survey have been more stable since 2013, these populations are still well below their historic maximum recorded values in 1978. In 2024, there were 868 Snowy Egrets counted, 73% lower than the 3,178 counted in 1978. There were 468 Black-crowned night herons counted in 2024, 68% lower than the 1,470 counted in 1978. The data show that both populations have failed to fully recover from a major decline that occurred between 1978 and 1983 when the Snowy Egret population decreased by over one-third and the Black-crowned night heron population declined by two-thirds. While not specifically linked to the NJ survey data, previous studies have identified numerous factors that can negatively affect waterbird populations and their breeding success, including nest-site competition with other coastal waterbirds, predation, invasive species, eutrophication, and the presence of pesticides and other environmental contaminants.3 Moving forward, climate change poses a substantial threat to waterbird habitat. This includes direct impacts to nests and young due to storms and flooding as well as decreased habitat suitability as sea-level rise inundates habitat. Nesting success of all colonial waterbirds can also be severely reduced by predators and specific types and excessive levels of human activity. The use of personal watercraft (e.g., jet skis) is of particular concern, as these vehicles interfere with waterbird feeding and nesting activities.

More Information

For more information on the natural history and protection efforts of these birds, visit the links below.

Snowy Egret: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Snowy_Egret/id

Black-crowned night heron: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Black-crowned_Night-Heron/id

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Wildlife Populations: Long-legged Wading Birds.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified January 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/wading-birds/.

Download the Data

The data used in Figures 1 is available to download here.

References

1US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Colonial-nesting Waterbirds: A glorious and gregarious group. Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usfwspubs/420. Accessed January 2025.

2Texas Parks and Wildlife. Black-crowned Night-heron. Available at http://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/species/bcnheron/. Accessed January 2025.

3Kushlan, J. A. et al. 2002. Waterbird Conservation for the Americas: The North American Waterbird Conservation Plan, Version 1. Waterbird Conservation for the Americas, Washington, DC, U.S.A. 78 pp. Available online at https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/north-america-waterbird-conservation-plan.pdf. Accessed January 2025.