In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Wildlife Populations-Peregrine Falcon

Background

The peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus anatum) bears the distinction of being the largest falcon in New Jersey, and the world’s fastest bird. Like other falcons, peregrines can be distinguished by their long, pointed wings and exceptional flight speed. Adult peregrines have slate gray to bluish backs and light-colored breasts with a fine brown horizontal barring that becomes lighter with age. Immature birds are brown above with a light-colored breast that is streaked vertically with brown markings.

Superior wing speed makes the peregrine extremely proficient at catching avian prey in flight. In New Jersey, their diet consists primarily of pigeons, songbirds, shorebirds, and ducks. Peregrines hunt by soaring high above their prey. Once their target is singled out, they fold their wings and drop headlong toward it. As the peregrine reaches its prey, its wings are extended in a braking motion while the legs are thrust forward in a pendulum motion. The prey is usually killed by the impact of this mid-air collision.

Historic records indicate that peregrines once nested on the cliffs above the Delaware Water Gap, and on the Palisades overlooking the Hudson River, however with the introduction and widespread use of DDT in the 1950s, peregrine populations plummeted. By 1964, peregrines had completely disappeared from the eastern half of the country, prompting federal and state governments to list the species as endangered.

With the ban of DDT in 1972, the then Division of Fish and Wildlife began a restoration program in New Jersey. Young peregrines were bred in captivity by the Peregrine Fund out of Cornell University and released along the coast between 1975 and 1980. Although the coastal marshes were not considered typical nesting habitat, an abundant prey base and freedom from predation by great horned owls provided a unique opportunity to restore the peregrine population. In 1980 the first wild nesting occurred at Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge in Brigantine. Today, the peregrine’s recovery in New Jersey continues at a slow, but steady pace. Each year, biologists from the NJDEP Fish and Wildlife’s Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP) band young falcons and gather information on nesting success and productivity. In addition, ENSP biologists continue to monitor the population to detect the presence of environmental contaminants. Since the majority of the adult population does not migrate, their health serves as a good indicator of the quality of our environment.

Status and Trends

In New Jersey today, peregrines nest along the Atlantic coast from Ocean to Cape May counties, on Delaware River bridges from Burlington to Cumberland Counties, and in natural cliff habitat in northeastern New Jersey.1 Prior to 2003, all nests were on human-made structures, such as nesting towers, water towers, large bridges, and high-rise buildings, however a milestone occurred in 2003 when a pair was confirmed nesting on the cliffs of the Palisades overlooking the Hudson River.

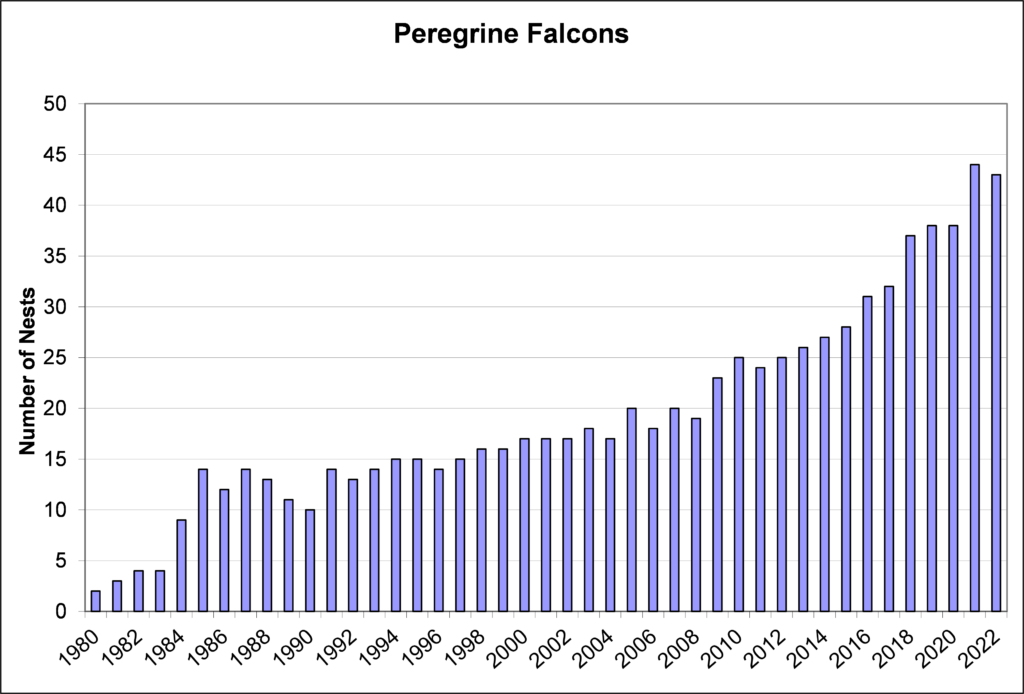

Since 1980, the peregrine population has been steadily increasing from two nesting pairs to a high of 44 nesting pairs in 2021 (See Figure 1). The population was 43 nesting pairs in 2022, of which 26 pairs were successful in producing 61 young for a productivity rate of 1.6 known young per active nest. The natural cliff and quarry population supported nine pairs during 2022 that produced 0.9 young/nest.

Figure 1. Number of Peregrine Falcon Nests from 1980 to 2022 in New Jersey.

The webcam (Union County Falcon Cam – Wildlife Education – Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey (conservewildlifenj.org) on the roof of the Union County courthouse provides live streaming of a falcon nest and two cameras (FALCON CAM – Palmyra Cove/Institute for Earth Observations) capture nesting boxes atop the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge and Burlington-Bristol Bridge.

Outlook and Implications

The restoration of the peregrine population in New Jersey marks an important conservation achievement. The tower and building nest sites are the consistent center of the population in New Jersey, without which the population would fluctuate widely year to year.1 Offspring from New Jersey falcons have also provided birds for reintroductions in the Appalachian Mountains, thereby accelerating the recovery process in the east.

Pairs that nest at cliff sites numbered nine in 2022, with just four pairs successful in fledging a known outcome of a total of eight chicks. Access to some sites made close monitoring difficult or impossible. Weather and intense storms did not seem to induce failures at cliff sites, however nest success and productivity remained lower than other regions. The highly variable nest success at the cliff territories continues to be a problem when considering the occupancy of historic habitat as important to a fully recovered population.2

Environmental contaminants such as pesticides, PCBs, and heavy metals continue to threaten sensitive components of our ecosystem, including the peregrine falcon. A 2009 analysis of peregrine eggs from Mid-Atlantic States showed that southern New Jersey peregrines continued to have higher levels of organochlorines and mercury than other regions, even those in similar salt marsh habitats.3Similarly, an analysis of eggs for flame retardant chemicals (polybrominated diphenyl ethers) found higher levels in NJ eggs than elsewhere (Wu et al., in review). Monitoring these contaminants is important for monitoring the health of New Jersey’s environment for wildlife and people.

More Information

- http://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/ensp/raptor_info.htm#peregrine

- http://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/peregrinecam/jcp-perfacts.htm

- http://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/ensphome.htm

References

Unless otherwise cited, the information in this report was provided by the DEP Division of Fish and Wildlife’s “Peregrine Falcon Research and Management Program in New Jersey, 2022”, which can be found at https://njdepwptest.net/wp-content/uploads/njfw/pefa21_report22.pdf and the Division of Fish and Wildlife’s Peregrine Facts webpage, which can be found at https://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/peregrinecam/jcp-perfacts.htm

1 Division of Fish and Wildlife Endangered and Nongame Species Program, “Endangered, Threatened and Rare Wildlife Conservation Projects/ Interim Report for Project Year September 1, 2013-August 31, 2014, https://www.nj.gov/dep/fgw/ensp/pdf/swgreports/swg_report-interim13-14.pdf Accessed 7/27/2023

2 Division of Fish and Wildlife, 2016. Peregrine Falcon Research and Management Program in New Jersey, 2016. http://www.conservewildlifenj.org/downloads/cwnj_784.pdf Accessed 7/27/2023.

3 Clark, K. E., Y. Zhao, and C. Kane. 2009. Organochlorine Pesticides, PCBs, Dioxins, and Metals in Post-term Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) Eggs from the Mid-Atlantic States, 1993–1999. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 57:174-184.

Wu 2023 Polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Submitted 2023.