In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Site Remediation

Background

The remediation of a contaminated site under New Jersey’s cleanup programs includes identifying the source, nature, and extent of contamination at a site, and conducting appropriate cleanup work. Remediation addresses a wide variety of site conditions, ranging from leaking underground home heating oil tanks to large, abandoned industrial sites with widespread environmental contamination. Remedial actions most often involve removing the source of contamination and decontaminating soil and water to protect human and ecological health. At times, the remediation involves capping the contaminated area with an impervious material for containment purposes and/or restricting future use for that property. New Jersey’s cleanup program has become a national model, and serious efforts are ongoing to reverse the effects of decades of mismanagement and discharges of contaminants and hazardous substances that have resulted in negative impacts to the environment and human health.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, growing public support for coordinated cleanup efforts and innovative state and federal laws enabled DEP to establish a progressive program to address New Jersey’s many contaminated sites. Beginning with the passage of the New Jersey Spill Compensation and Control Act1 (“Spill Act”) in 1976, the State initiated the first program in the country to clean up, or remediate, contaminated sites, whether conducted by responsible parties or with public funds dedicated through the Spill Act, that posed a danger to human health and the environment.

As the universe of known contaminated sites in New Jersey increased, DEP expanded its cleanup efforts to meet the challenges posed by a variety of pollution problems. The passage of several key state laws facilitated these endeavors, including the Environmental Cleanup Responsibility Act (later replaced by the Industrial Site Recovery Act2) , and additions to the Water Pollution Control Act3 (see page 56 for details regarding the Underground Storage Tank Act), and the Brownfield and Contaminated Site Remediation Act4 (“Brownfield Act”) of 1998, and further refined the overall remedial process and stimulated cleanup and reuse of additional brownfield sites.

By 1994, DEP identified approximately 12,000 sites in New Jersey, including both known and suspected contaminated sites. The number of active cases in New Jersey peaked at over 20,000 in 2008, and this number was often cited as DEP’s “backlog.” This increase was attributed to several factors, including a growing reliance on the use of hazardous materials by industries, increased awareness of the risk posed by certain chemicals, and new technologies that were able to detect these chemicals.

This report will cover several indicators that help to assess the amount of ongoing effort and the work that remains to remediate contaminated sites in New Jersey. The indicators that are explored are described in detail below and include:

- Active Cases

- Cases Completed

- Number of Cases with a Response Action Outcome(s) (RAO)

- Unregulated Heating Oil Tank Cases (UHOL)

- Cases in Compulsory Direct Oversight

- Cases without an assigned Licensed Site Remediation Professional (LSRP)

- Cases with an Administrative Consent Order (ACO)

- Cases in Compliance with an ACO

Site Remediation Reform Act

In 2009, faced with the challenge of ensuring that up to 20,000 active cases in New Jersey were properly remediated in a timely manner, DEP worked closely with the New Jersey Legislature and stakeholders to develop legislation to reform the process used to conduct environmental investigations and cleanups. As a result, in May 2009, the Site Remediation Reform Act5 (SRRA) was signed into law. The legislation that created SRRA also amended other statutes such as the Brownfield Act and the Spill Act. The amendments to the Brownfield Act at N.J.S.A. 58:10B-1.3 included establishing an affirmative obligation on persons to remediate any discharge for which they would be liable pursuant to the Spill Act, Industrial Site Recovery Act , and Underground Storage Tank Act.

In August 2019, after collaboration among the New Jersey Legislature, DEP, and stakeholders, Governor Philip Murphy signed legislation updating SRRA (commonly referred to as SRRA 2.0). This update improves the effectiveness of the LSRP program and further streamlines the remediation process in New Jersey while maintaining stringent cleanup standards.

SRRA established a program for the licensing of LSRPs, who have the responsibility to oversee environmental investigations and cleanups. The law established that LSRPs can move a remediation forward without DEP approval, except under limited circumstances. The law was phased in over three years, becoming fully effective in May 2012. Since then, with limited exceptions, remediating parties are required to use the services of an LSRP to proceed with the cleanup of discharges that occur at their site.

While the law resulted in a process change, there was no change to stringent technical requirements, remediation standards, or the DEP’s authority. The DEP ensures that remediating parties comply with all applicable regulations, while the day-to-day management of the remediation of the site is overseen by the LSRP. For sites subject to SRRA, the final remediation document that is issued by the LSRP when the remediation is complete is a Response Action Outcome (RAO).

SRRA also established the Site Remediation Professional Licensing Board (SRPL Board), which is the body that issues LSRP licenses to qualified individuals. The SRPL Board also oversees the professional conduct of LSRPs, who are bound by a strict code of conduct6. A violation of the code of conduct could result in the assessment of penalties as well as suspension or revocation of the LSRP’s license by the SRPL Board.

For cases where a discharge was discovered before May 7, 1999, SRRA established the statutory timeframe to complete the remedial investigation by May 7, 2014. SRRA was later amended to extend this timeframe to May 7, 2016 for a subset of these cases.

SRRA also granted DEP the authority to establish mandatory remediation timeframes for the completion of key phases of site remediation. For cases where the discharge is discovered after May 7, 1999, the remedial investigation is to be completed within seven years of the date the discharge is discovered.

Remedial actions for cases with only soil contamination are required to be completed five years after the original timeframe to complete the remedial investigation and seven years after the original timeframe to complete the remedial investigation when multiple media are impacted. For sites subject to the May 7, 2014 statutory timeframe mentioned above, remedial actions were required to be completed by February 6, 2021 for cases with only soil contamination and May 7, 2021 when multiple media were impacted. For sites granted the extension to May 2016, remedial actions were required to be completed by May 7, 2021 for cases with only soil contamination and May 7, 2023 when multiple media were impacted.

Except for the statutory timeframe, extensions can be requested for all timeframes mentioned above. Cases may also lengthen the time to complete a remedial phase based on site specific scenarios. Another factor that affected the time to complete the remediation is the COVID-19 pandemic extension. Executive Order 103 granted a one year extension to timeframes for cases subject to the statutory timeframes and 455 days to timeframes for all other cases.

SRRA requires DEP to undertake direct oversight in cases where the remediating party has missed a mandatory or statutory timeframe or when there is significant risk to public health and the environment.

Other Case Types

Unregulated heating oil tank systems (UHOTs) are heating oil underground and above-ground storage tank systems that service residential buildings and those systems with a capacity of 2,000 gallons or less for on-site consumption at non-residential sites. While the tanks themselves are considered unregulated, there is an obligation to remediate any discharges from UHOTs pursuant to the Spill Act. DEP tracks these cases separately from other remediation cases.

UHOT cases are typically lower risk cleanup projects and, pursuant to SRRA, do not require LSRP oversight. As such, DEP reviews the remediation reports and when remediation is complete, issues the final remediation document in the form of a No Further Action (NFA letter). Because these cleanups are often associated with real estate transactions, DEP strives to review these cases and issue an NFA letter as quickly as possible. NFAs are typically issued within two weeks of receipt of the final report.

The balance of additional contaminated sites overseen by DEP case managers include:

- Sites being remediated by DEP (or its contractors) using public funds;

- Federal sites (i.e., RCRA, CERCLA, Federal Facilities) that are being overseen by EPA and DEP; and

- Direct oversight cases where a case manager is assigned to oversee the remediation due to a missed timeframe.

Emissions control technology installed at landfill for site remediation.

Status and Trends

The traditional DEP and LSRP oversight programs were operating simultaneously during the initial implementation period that took place between May 2009 and May 2012. New cases were automatically entered into the LSRP program and existing cases were given three years to transition into the new program. During this transition period, the metrics used for tracking changed. Since the implementation of SRRA, the DEP tracks “cases,” which can include multiple regulatory or contamination issues at one site. For example, while a gas station may represent a single site, discharge(s) that occurred for each successive owner/operator represent an individual case.

Active Cases

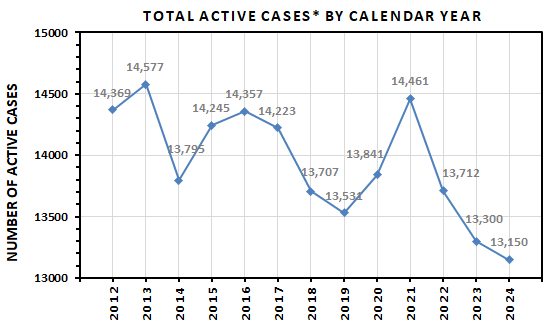

The average total active case count from May 2012 to December 2024 is 13,944 cases per year. This includes all case types noted in the preceding section. The total number of active cases during this time was the greatest in 2013 (14,577) and the lowest in 2024 (13,150). The number of cases can fluctuate from year to year due to an increase or decrease in real estate transactions which can spur identification of new cases or result in the remediation of others. For example, the increase in active cases for 2021, as compared to 2020, is possibly due to an increase in real estate transactions after COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. See Figure 1, “Total Active Cases by Calendar Year” below.

Additional fluctuations may occur when timeframes are reached for batches of LSRP cases. From May 2012 to December 2024, the average number of active LSRP cases per year is 10,560 cases. In May 2024, cases with statutory timeframes were required to complete the remedial action. In June 2024, there were 9,539 active LSRP cases. The continuing decrease in the number of active LSRP cases can be attributed to the May deadline.

From 2014 to 2024, the average number of active UHOT cases per year is 864.

Figure 1. Total Active Cases by Calendar Year

*Total Active Cases refers to all site remediation cases recorded by the DEP, including (a) the LSRP program, (b) UHOT, (c) sites using public funds to complete the remediation, and (d) other known contaminated sites with some level of DEP oversight.

Cases Completed

“Completed cases” are those for which a final remediation document has been issued (either a DEP-issued NFA letter or an LSRP-issued RAO). The total number of cases completed per year peaked in 2018 at 5,061, with an average number of cases completed from 2012 to 2024 of 4,331 per year. As discussed below, the majority of these are UHOT cases.

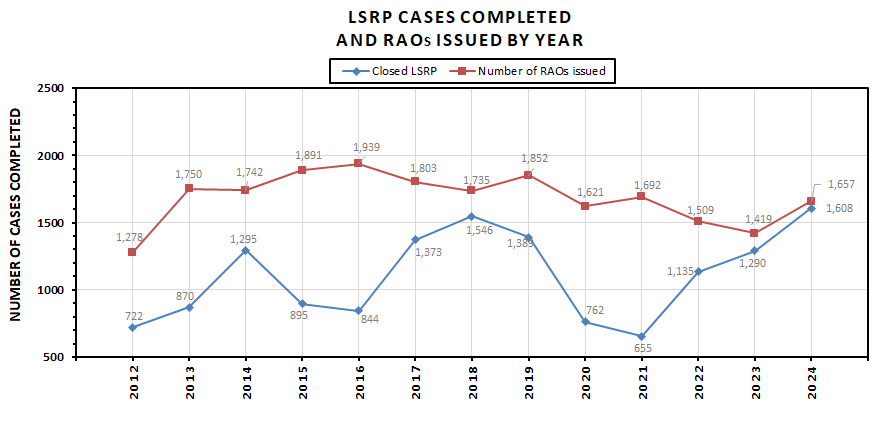

LSRP Cases

DEP expected the number of LSRP cases completed to generally increase each year. The number did increase from 722 in 2012 to a peak of 1,295 in 2014, then decreased to 844 in 2016. The peak in 2014 is likely due to the statutory timeframe set forth in SRRA to complete the remedial investigation for cases addressing discharges discovered before May 1999. The number of LSRP cases completed peaked again at 1,546 in 2018 and then decreased to 762 completed cases in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in extensions to remediation timeframes for many cases, which impacted the number of cases completed in 2020. In 2024, completed LSRP cases totaled 1,608, the greatest number since these records began in 2012. See Figure 2, below.

Figure 2. Licensed Site Remediation Professional (LSRP) Cases Completed and Response Action Outcomes (RAOs) Issued by Year.

The number of Response Action Outcomes (RAOs) issued by LSRPs is different from cases completed, as there can be more than one RAO associated with a case. For example, an LSRP can issue an RAO for all soil contamination associated with a case, and later issue an RAO for ground water contamination associated with the same case. From 2012 through 2024, LSRPs have issued more than 21,000 RAOs, certifying that a remediation was completed in accordance with New Jersey’s statutes and DEP’s rules and standards. The number of RAOs issued annually initially was increasing, peaking at 1,939 RAOs issued in 2016. Since then, the number of RAOs issued has been slowly decreasing. The significant decrease in the number of RAOs issued in 2020 can be attributed to extensions provided due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are several reasons why the number of cases closed or the number of RAOs issued may fluctuate over the years. For the first ten years of the program, cases requiring less complicated remediation or remediations that could be implemented more quickly have been completed and had RAOs issued. Other, more complicated cases may require longer, more sophisticated remediation.

As noted above and below, cases that were subject to statutory timeframes established in SRRA to complete the remedial investigation by either May 2014 or May 2016 were required to complete the remedial action by May 2024. In 2024, data shows that 1,608 LSRP cases were completed and 1,657 RAOs were issued by LSRPs.

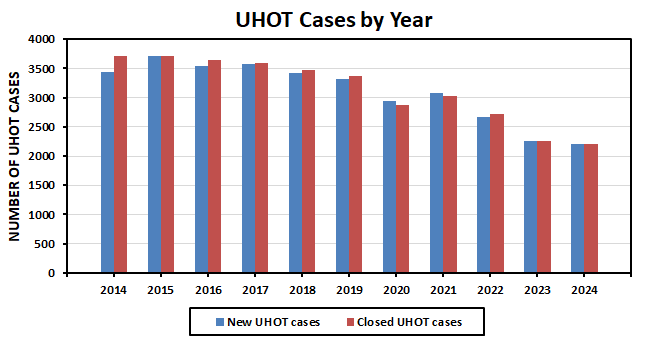

Unregulated Heating Oil Tank (UHOT) Cases

An unregulated heating oil tank (UHOT) being removed from underground.

UHOT cases represent a smaller percentage of active cases. From 2014 to 2024, the average number of active UHOT cases is 864 per year. However, over 34,500 heating oil tank cleanups were completed in this timeframe with an average of 3,141 per year. As noted above, fluctuations in the total number of cases are often caused by changes in the real estate market, particularly for UHOT cases.

Figure 3. Unregulated Heating Oil Tank (UHOT) Cases by Year.

Direct Oversight

DEP’s role in the LSRP program is to regulate remediating parties through its remediation regulations. In part, this includes monitoring remediation timeframes to ensure that remediation occurs in a timely manner.

SRRA set forth a statutory timeframe for certain remediations that were initiated prior to May 7, 1999. For these cases, SRRA required that the remedial investigation be completed within 10 years of the date of enactment of SRRA, or by May 7, 2014. In January 2014, SRRA was amended to allow persons remediating certain sites subject to the May 7, 2014, statutory timeframe to complete the remedial investigation to request an extension to instead complete the remedial investigation by May 7, 2016.

Based on a triggering event (e.g., date of a discharge), cases are assigned regulatory and mandatory timeframes. Regulatory timeframes are those that serve as an early warning system for remediating parties to keep their remediation on track. Mandatory timeframes are those that must be met for the remediation to remain in compliance. If a remediating party missed either the May 7, 2014 or May 7, 2016 statutory timeframe, or misses a mandatory timeframe as outlined in SRRA DEP regulations, the remediation is out of compliance and subject to compulsory direct oversight requirements. Compulsory direct oversight requirements, outlined in the Administrative Requirements for the Remediation of Contaminated Sites 7 (ARRCS), are a much more proscriptive process for the remediating party and include, but are not limited to, establishing a remediation funding source, creating a public participation plan, and implementing a remedial action(s) that DEP selects. It should be noted that cases that miss a statutory or mandatory timeframe remain in compulsory direct oversight until they are closed.

The direct oversight case inventory was most recently captured in 2023. At the end of 2023, there were 4,563 active LSRP cases that missed one or more mandatory timeframes, which triggered compulsory direct oversight. Of the cases in compulsory direct oversight, 3,206 have retained an LSRP to conduct remediation. This metric is important to DEP because LSRPs must evaluate any impacts to nearby human and ecological receptors, as an LSRP’s highest priority in the performance of professional services is the protection of public health and safety and the environment as set forth in the Regulations of the New Jersey Site Remediation Professional Licensing Board at N.J.A.C. 7:26I-6.2.8 When a case has a retained LSRP, the LSRP is responsible for ensuring that the proper steps are taken to bring the remediation into compliance and continue working through the remediation process while adhering to timeframes. Of the 1,357 cases that did not have a retained LSRP at the end of 2023, 916 had never retained an LSRP. Of the remaining 441 cases, some may have been within the 45-day window to retain an LSRP. For the cases in compulsory direct oversight that have not retained an LSRP, DEP conducts outreach and education to remediating parties regarding their obligation to retain an LSRP and conduct remediation. DEP may send Notices of Violation if the remediating party does not comply and may explore other enforcement options.

Some cases in compulsory direct oversight may move towards an Administrative Consent Order (ACO), a legal agreement between DEP and a responsible party that addresses violations of environmental laws and re-establishes compliance with environmental regulations. An ACO is used to set new timeframes or amend other conditions of compulsory direct oversight. As of December 2023, 264 cases have signed ACOs. A subset of these cases may have executed Adjusted Direct Oversight Administrative Consent Orders (Adjusted DO ACOs), which allow for the remediating party and DEP to agree to new timeframes and adjustments to other direct oversight requirements set forth in the applicable rules (ARRCS). Without an Adjusted DO ACO, the remediation must strictly comply with all of the direct oversight requirements as set forth in the rules (N.J.A.C. 7:26C-14.2(b)). As of December 2023, there were 210 cases in compliance with an ACO. It should be noted that there is no break in the remediation process, the remediating party of a site in direct oversight and their retained LSRP are still required to continue with the remediation, even if they are working toward an ACO with the DEP.

Outlook and Implications

New Jersey has a long history of manufacturing industries, particularly petroleum, chemical, pharmaceutical, and agricultural. Through successful implementation of SRRA, DEP, LSRPs, and the regulated community are addressing historical contamination efficiently, protecting the public health and the environment, and sites are being returned to beneficial community use.

Today, due to the reforms set forth in law and the diligent work of LSRPs and DEP staff, more contaminated sites are being actively remediated than ever before, and they are being cleaned up faster. Although the active cases count is increasing (because DEP is proactively identifying new cases), a decreasing trend is expected in the future as timeframes are reached and more remedial actions are completed for LSRP cases. The increase in the number of cases completed indicates that contamination is being addressed and remediation activities are concluding. Similarly, the increasing number of RAOs issued by LSRPs indicates that the remediation portions of sites or entire sites are moving forward, and portions of properties are being readied for redevelopment.

DEP is continuously re-evaluating the program to ensure its continued success and protecting the public health and environment of the State of New Jersey.

More Information

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Site Remediation.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified April 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/site-remediation/.

Download the Data

The data used in Figures 1-3 are available to download here.

References

1New Jersey Spill Compensation and Control Act, N.J.S.A. 58:10-23.11 et seq. https://www.nj.gov/dep/enforcement/dp/downloads/NJ_Spill_Act.pdf Accessed 6/6/2024.

2Industrial Site Recovery Act, N.J.S.A. 13:1K-6 et seq. https://www.nj.gov/dep/srp/regs/statutes/isra.pdf Accessed 6/10/2024.

3Water Pollution Control Act, N.J.S.A. 58:10A-21 et seq. https://njdepwptest.net/wp-content/uploads/srp/wpca_58_10a.pdf Accessed 6/10/2024.

4Brownfield and Contaminated site Remediation Act, N.J.S.A. 58:10B-1 et seq. https://www.nj.gov/dep/srp/regs/statutes/bcsra.pdf Accessed 6/10/2024.

5Site Remediation Reform Act, N.J.S.A. 58:10C-1 et seq. https://www.nj.gov/dep/srp/regs/statutes/srra.pdf Accessed 6/10/2024

6LSRP Code of Conduct, Site Remediation Reform Act 58:10C-16. https://www.nj.gov/lsrpboard/board/prof_conduct/code_of_conduct_provisions.pdf Accessed 6/6/2024

7Administrative Requirements for the Remediation of Contaminated Sites, N.J.A.C. 7:26C-14 https://njdepwptest.net/wp-content/uploads/rules/rules/njac7_26c.pdf Accessed 6/10/2024.

8Regulations of the New Jersey Site Remediation Professional Licensing Board N.J.A.C.7:26I https://njdepwptest.net/wp-content/uploads/rules/rules/njac7_26i.pdf Accessed 7/11/2024.