In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Seabirds

Background

Seabirds are adapted for marine life, occurring in both nearshore and offshore environments. They are one of two groups of colonial-nesting waterbirds highlighted in New Jersey’s Environmental Trends Report series (see Long-Legged Wading Birds report). Colonial-nesting waterbird is a collective term used to refer to a large number of species that share two common characteristics:

(1) They tend to nest in close proximity to one another during the breeding season.

(2) They gather most of their food from the water, mainly fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Colonial waterbirds have attracted the attention of scientists, conservationists, and the public, especially since the early 1900s when plume hunters nearly drove many species to extinction. Although the populations of many species rebounded in the middle part of the 20th century, major losses, diminished resources of prey fish resulting from overexploitation, and alteration of freshwater and coastal wetland habitats still threaten the long-term sustainability of many colonial waterbirds. Many of these species have not recovered from these impacts, including some that have been listed as threatened or endangered in the United States or in New Jersey.1 These birds are important predators, feeding near the top of the food chain. They serve as valuable indicators of environmental quality, including resource abundance and health; levels of toxic substances, such as organic contaminants and heavy metals; and levels of human disturbance.

Some seabird species, such as albatrosses and frigatebirds, are so well adapted to the marine environment that they spend most of their lives at sea, returning to land only to nest. Others, such as gulls and terns, are confined to the interface between land and sea, feeding during the day and roosting on land. The Department tracks a number of populations of these birds, including the Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla), the Herring Gull (Larus argentatus), and the Forster’s Tern (Sterna forsteri).

Gulls possess exceptional flying ability and are often seen swimming, occasionally diving underwater. Increasing gull populations in North America during the past century have led to a variety of problems for different segments of society. Gulls can cause damage to agricultural crops and threaten human safety at and near airports; they are involved in more collisions with aircraft than any other bird group due to their high numbers and wide distribution. They are also often considered a nuisance species due to their propensity to nest near human populations and seek food from people eating outdoors. In addition, gulls are predators of several birds during the breeding season; expanding and colonizing gull populations may have detrimental effects on the breeding performance of other species.2

The Laughing Gull is a small, black-hooded gull; its light, buoyant flight and laughing call are a familiar sight and sound along New Jersey’s coast.3 Laughing Gull colonies breed primarily in Atlantic coastal marshes, some of which may harbor thousands of individuals. The nest, made largely from grasses, is constructed on the ground, and the three or four greenish eggs are incubated for about three weeks.4

The Herring Gull, a large white bird with a light gray back and wings, pink legs, and a yellow beak with a red dot at the tip, is a year-round resident of New Jersey. This species, like the Laughing Gull, also generally nests in large colonies. Both species are generalist predators and will feed on a variety of fishes, invertebrates, and other seabirds.5 They can also be opportunistic scavengers, feeding on carrion and human refuse.6

Terns are small to medium-sized birds, typically with grey or white plumage and black markings on the head, pointed bills, deeply forked tails, and webbed feet. In comparison with gulls, they are lighter bodied, more streamlined, and more agile. Forster’s Tern breeds primarily in marshes along New Jersey’s Atlantic coast. The diet of the Forster’s Tern consists mainly of small fish and occasional invertebrates. While hunting, this species dives directly into water from heights as high as 25 feet above the water surface.7

Survey Description

For nearly five decades, NJDEP Fish and Wildlife (NJFW) has monitored the nesting populations of colonial waterbirds through a combination of ground and aerial surveys.

Ground surveys are primarily conducted on non-marsh islands, where nesting areas are easier to access. This typically targets long-legged wading bird species that readily nest off of marsh islands. This includes inland areas and barrier islands, but are often in human-dominated landscapes, including residential properties, local parks, and similar areas. These surveys highlight the plasticity of some species and provide insights for bird conservation strategies if the marsh environment becomes less suitable for nesting in the future. Observers tally the number of adults, nests, and fledged chicks. Ground survey data are not included in the data trends and figures below, as it is not as consistently or comprehensively collected, and therefore not suitable for long-term trends analyses.

Aerial surveys have been conducted since 1976 and are used for the trends summarized below in this report. These surveys follow a protocol that entails counting all adult birds associated with a landmass in the marshes and back bay habitats from Mantoloking to Cape May by helicopter. Nesting by these species in other portions of the state are not included in this dataset. However, the majority of the nesting sites for these species are captured on this survey. The protocol is consistent and appropriate to establish long-term trends. The trends reported below are based on population indices, and should not be considered population estimates, which require much more intensive surveying efforts for a sufficient dataset and are notoriously difficult to obtain. The trends instead summarize population indices, which are a one-time count conducted each season. Notably, aerial surveys tend to underestimate the number of adults present, especially for those birds with dark plumage, which can be difficult to see through the cover of vegetation.

Status and Trends

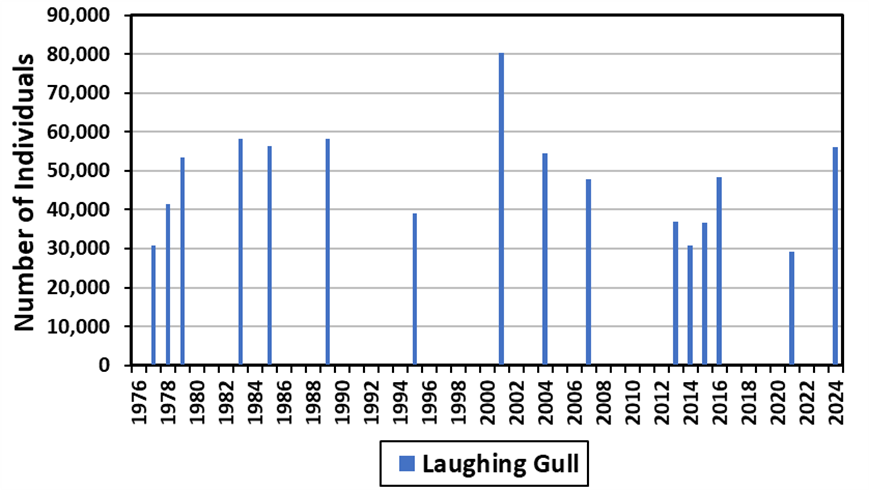

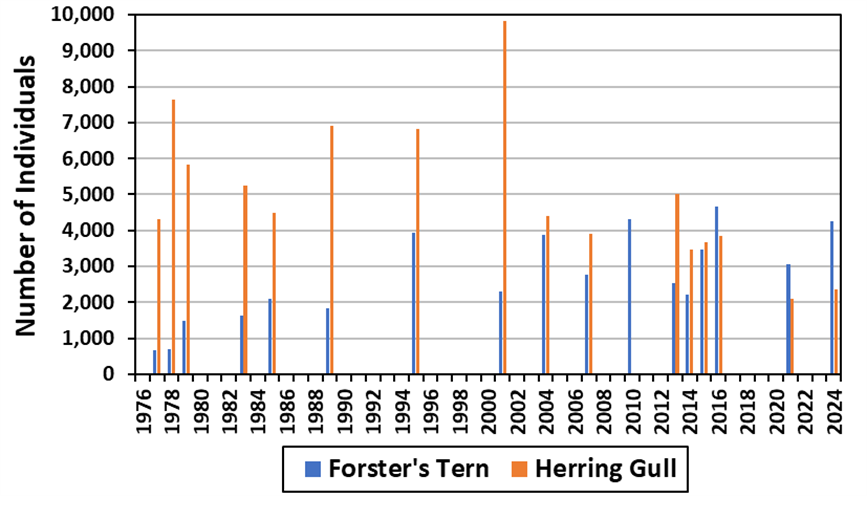

Figures 2 and 3 below show the number of individuals for each species by year. The data, collected by NJDEP Fish and Wildlife (NJFW), show fluctuations from year to year, with especially large gull counts in 2001. The Forster’s Tern and Herring Gull are shown together in Figure 2 based on similar adult counts, while the Laughing Gull numbers are much higher, requiring a different y-axis scale shown in Figure 3.

The Herring Gull tallies (Figure 2) have fluctuated over time, with a significant decline from 1977 to 2024 (Kendall Tau Correlation, rho = -0.53, p <0.05). In the earliest data collected, the three-year average from 1977 to 1979 was 5,928 adults. In the late 1980s and mid 1990s the counts increased to over 6,800 individuals, peaking at 9,814 in 2001. The counts in the survey area subsequently decreased to a three-year average of 3,656 from 2014 to 2016. As of 2024, there were only 2,346 individuals. On the other hand, the number of Forster’s Terns (Figure 2) tallied on the surveys has increased significantly since 1977 (Kendall Tau Correlation, rho = 0.63, p < 0.05) with 4,244 counted in 2024.

Figure 1. Number of Herring Gull and Forster’s Tern individuals as counted from aerial surveys. Years without counts represent years when surveys were not conducted.

The Laughing Gull population (Figure 3) has fluctuated from year to year without showing a significant increase or decrease over time. There were 56,103 individuals counted in the 2024 New Jersey aerial survey. Nearby regions, however, are showing a different trend. In 2013, the Center for Conservation Biology reported a substantial threat to the Laughing Gull population in the breeding grounds on the coast of the lower Delmarva Peninsula. Significant tidal events since the early 2000’s due to rising seas repeatedly washed out eggs and nests along the Delmarva Peninsula and Laughing Gull populations in that area declined by over 80% from 2003 to 2013.8 In the decade since, additional losses have been documented and the population decline is now estimated at more than 90%.99 This highlights the importance of ensuring the stability of this species population in New Jersey.

Figure 2. Number of Laughing Gull individuals as counted from aerial surveys. Years without counts represent years when surveys were not conducted.

Outlook and Implications

While the populations of some seabird species appear to be stable, they nevertheless face substantial, ongoing threats. This includes direct human impacts that cause habitat to become fragmented, altered, or lost, as well as indirect human impacts to habitat arising from climate change, like sea-level rise, changing sea surface temperatures, shifting tidal conditions, and salinity changes.10 Other threats to seabirds include depredation of colonies by predators,11 direct mortality from entanglement in commercial fishing gear,12 altered timing and availability of prey fish,13 direct and indirect impacts from anthropogenic fishing activities,14 and chronic pollution like oil associated with increased tanker traffic also threaten these ground-nesting species.15,16 Restoration and habitat management projects, such as living shorelines and beneficial reuse of dredged materials, may help mitigate some of these challenges.

More Information

For more information on the natural history and protection efforts of these birds, visit the links below.

Laughing Gulls: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Laughing_Gull/id

Herring Gulls: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Herring_Gull/id

Forster’s Tern: http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Forsters_Tern/id

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Wildlife Populations: Seabirds.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified January 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/seabirds/.

Download the Data

The data used in Figures 1 and 2 are available to download here.

References

1US Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Colonial-nesting Waterbirds: A glorious and gregarious group. Available at https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usfwspubs/420. Accessed January 2025.

2The Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management. Gulls. Available at https://icwdm.org/?s=gulls. Accessed January 2025.

3Burger, J. (2020). Laughing Gull (Leucophaeus atricilla), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.laugul.01. Accessed January 2025.

4National Audubon Society. Laughing Gull Audubon Field Guide. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/laughing-gull. Accessed January 2025.

5National Audubon Society. Herring Gull Audubon Field Guide. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/herring-gull. Accessed January 2025.

6Cornell Lab of Ornithology, All About Birds, (Herring Gull). Online: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Herring_Gull/id. Accessed online August 2024.

7National Audubon Society. Forster’s Tern Audubon Field Guide. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/forsters-tern. Accessed January 2025.

8The Center for Conservation Biology. Available at: http://www.ccbbirds.org/2013/11/18/laughing-gulls-match-rising-seas/. Accessed January 2025.

9The Center for Conservation Biology. Available at: https://ccbbirds.org/2023/10/03/laughing-gulls-continue-to-lose-ground/. Accessed January 2025.

10Erwin, R. M., Sanders, G. M., Prosser, D. J. and Cahoon, D. R. 2006. High tides and rising seas: potential effects on estuarine waterbirds. Studies in Avian Biology, 32, p.214. https://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/sab/sab_032.pdf

11Towns, D.R., Byrd, G.V., Jones, H.P., Rauzon, M.J., Russell, J.C. and Wilcox, C., 2011. Impacts of introduced predators on seabirds. Seabird islands: ecology, invasion, and restoration, pp.56-90.

12Žydelis, R., Small, C. and French, G., 2013. The incidental catch of seabirds in gillnet fisheries: a global review. Biological Conservation, 162, pp.76-88.

13Massaro, M., Chardine, J.W., Jones, I.L. and Robertson, G.J., 2000. Delayed capelin (Mallotus villosus) availability influences predatory behaviour of large gulls on black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla), causing a reduction in kittiwake breeding success. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 78(9), pp.1588-1596.

14Wagner, E.L. and Boersma, P.D., 2011. Effects of fisheries on seabird community ecology. Reviews in fisheries science, 19(3), pp.157-167.

15Croxall, J.P., Butchart, S.H., Lascelles, B.E.N., Stattersfield, A.J., Sullivan, B.E.N., Symes, A. and Taylor, P.H.I.L., 2012. Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird Conservation International, 22(1), pp.1-34.

16Richard, F.J., Gigauri, M., Bellini, G., Rojas, O. and Runde, A., 2021. Warning on nine pollutants and their effects on avian communities. Global Ecology and Conservation, 32, p.e01898.