In This Report:

Contact Us:

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Beach Replenishment

Background

New Jersey’s beaches play a critical role in protecting people and property from coastal storm hazards. Due to its geography, New Jersey is in the path of hurricanes (tropical storms) and nor’easters (extratropical storms). Beaches act as a buffer between the surf and the homes, businesses, and infrastructure along the coast. In addition, beaches provide recreation for beachgoers and fishermen and help support a multibillion-dollar tourism industry. In 2022, direct visitor spending through travel and tourism was $45.4 billion to the state. In addition, employment supported directly by visitor activity reached 310,450 jobs in 2022. Furthermore, tourism generated $5 billion in state and local government taxes. A regional breakdown of tourism shows that 19.9 percent of total tourism direct sales occur in Atlantic County, with the Southern Shore Region (Cape May and Cumberland counties) and the Shore Region (Monmouth and Ocean counties), contributing 10.7 percent and 17 percent respectively.1

Tourists and beachgoers visiting Long Beach, NJ (Getty Images)

Attention to shoreline management is becoming more important as the sea level along the New Jersey coast rises due to climate change and subsidence (see Climate Change in New Jersey: Trends in Temperature and Sea Level, in this Environmental Trends series). Rising seas are likely to accelerate beach erosion and coastal inundation. According to the Report of the 2019 Science and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP),2 sea levels are rising at a greater rate in New Jersey than in other parts of the world.

Past examination of shoreline positions along the Atlantic Ocean in New Jersey from 1836 to 1985 revealed the trend of shoreline erosion. Since that time, notable advances in shoreline position and increases in sand volumes have been documented statewide by the New Jersey Beach Profile Network conducted for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (Department or NJDEP) by Stockton University.3 Virtually all those advances and increases are either directly or indirectly related to the inception of the Coastal Storm Damage Reduction and Coastal Storm Risk Management projects, most of which are in partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Historically, New Jersey built seawalls, groins, and jetties as a defense against beach erosion. Today, in most cases, beach replenishment and other nature-based solutions are preferred to hard structures such as seawalls and bulkheads, because it provides the basis for restoration of landforms and biota, and for recovery of lost environmental heritage. Coastal sand dunes are an integral part of a well-planned coastal defense system. Coastal sand dunes provide habitat for a variety of species in addition to acting as reservoirs of sand to help maintain beach equilibrium and preserve the ability of the beach to respond naturally to storm events. They are vitally important during moderate to large storms when the dissipation created by the sand bars is insufficient to prevent the waves from attacking the beach berm.4

Beach replenishment (or beach nourishment) is the placement of large quantities of sand on an eroding beach to advance the shoreline seaward and increase its elevation as well as to construct dunes. These engineered beaches and dunes act as a barrier against wind and wave attack and are designed to absorb much of the storm energy before it can reach buildings and infrastructure. Additionally, the replenished material reintroduces sand originally displaced from the sediment budget. Typically, an engineered beach and dune design includes periodic nourishment to replace the sand that has been eroded from the engineered beach and dune design template – often into offshore bar systems and alongshore. Fortunately, sand transported outside of the design template can still benefit the project, as it can dampen the wave energy as it approaches the shoreline. Essentially, the periodic nourishment subsequently added to beaches is used as a surrogate for quantities of sand lost from beaches due to erosion. Secondary benefits of beach replenishment include providing added recreational area and, in some cases, reintroducing environmental habitat for endangered species.

New Jersey’s beaches serve as a buffer between ocean waves and landward development but are a vital recreational resource as well. As a result, the state has an interest in maintaining its beaches for public recreational use and shore protection. Interest in shore protection in New Jersey began in the mid-1800s. The state’s shorelines, being within easy reach of the burgeoning populations of New York City and Philadelphia, were the first to experience intense coastal development. Oceanfront dunes were often leveled or developed upon, and freshwater ponds between dunes were filled to create building lots. Rapid development ensued without awareness of coastal hazards, storm vulnerability, or beach erosion. A period of intense storm and hurricane activity between 1915 and 1921, in which three hurricanes and four tropical storms passed within several nautical miles of the coasts of New Jersey, highlighted the sensitivity of newly developed shore regions to beach erosion. Soon thereafter, the early versions of coastal engineering projects such as bulkheads, groins, and revetments were built to armor the coast, trap sand, and slow the erosion process. Some projects proved to be more effective than others.5 Piecemeal approaches often aggravated the problem on adjacent shorelines. The state began approaching shore protection on a regional basis within areas affected by similar coastal processes with the development of the Shore Protection Master Plan in 1981.6 This approach considers the potential for any one shore erosion control program to adversely affect another.

Aerial scene showing a New Jersey beach with extensive landward development (Getty Images)

Many programs within the Department are charged with managing coastal resources such as protecting surf clam and shorebird habitats, minimizing impacts from development, and minimizing development in hazard areas. Together, these programs comprise NJDEP’s Coastal Management Program.7 The Coastal Management Program is comprised of a network of offices within the NJDEP that serve distinct functions yet share responsibilities that influence the state of New Jersey’s coast.

The core offices of the Coastal Management Program are the Office of Climate Resilience and Watershed & Land Management (WLM). The Office of Climate Resilience is tasked with overall administration and coordination of the Coastal Management Program and ensuring that the impacts of climate change are considered in long-term decision-making.

WLM includes multiple core offices of the Coastal Management Program, and particularly those with the most significant involvement with beach replenishment and shore protection. WLM’s Division of Resilience Engineering and Construction, Office of Coastal Engineering, manages shore protection and storm damage reduction projects that protect the resource areas as well as the developed areas. The Office of Coastal Engineering is responsible for administering shore protection projects associated with the protection, stabilization, restoration, and maintenance of the shore that are consistent with the Shore Protection Master Plan as well as the policies and guidelines of the Coastal Management Program. To successfully and efficiently administer these projects, the Shore Protection Fund was created to provide a stable funding source to finance these projects. The Office of Coastal Engineering (OCE) partners with federal agencies such as the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and FEMA as well as county and local municipalities when implementing these crucial projects.

To ensure these projects are administered with the proper regulatory authority, OCE coordinates closely with WLM’s Division of Land Resource Protection, another program that comprises the Coastal Zone Management Program, the Division of Land Resource Protection ensures compliance with various land use rules and regulations such as the Coastal Area Facility Review Act (CAFRA)(N.J.S.A. 13:19), the Waterfront Development Act (N.J.S.A. 12:5-3) and the Wetlands Act of 1970 (N.J.S.A. 13:9A).

Status and Trends

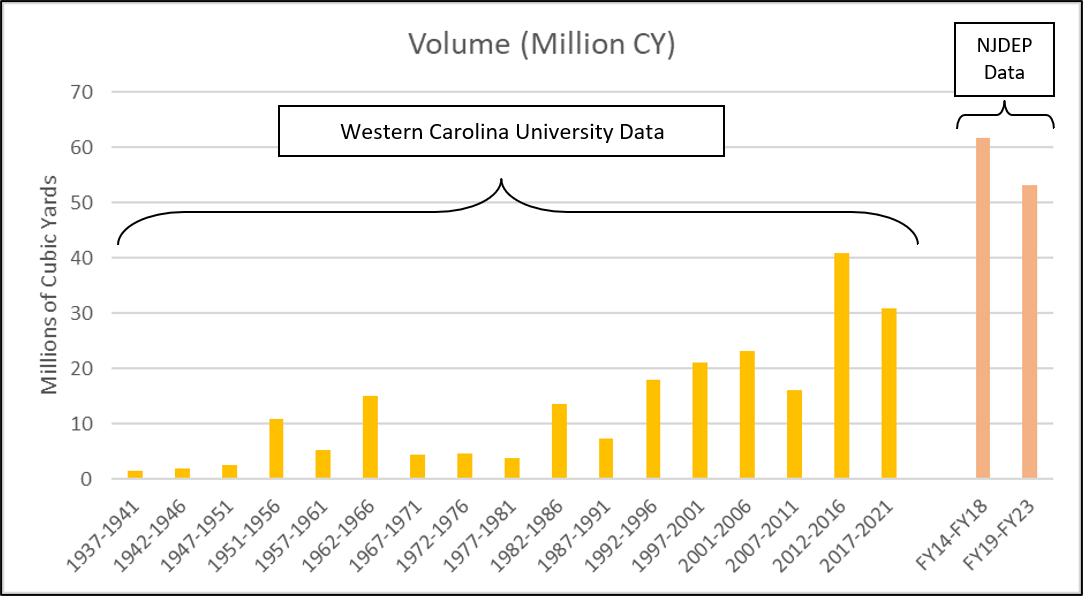

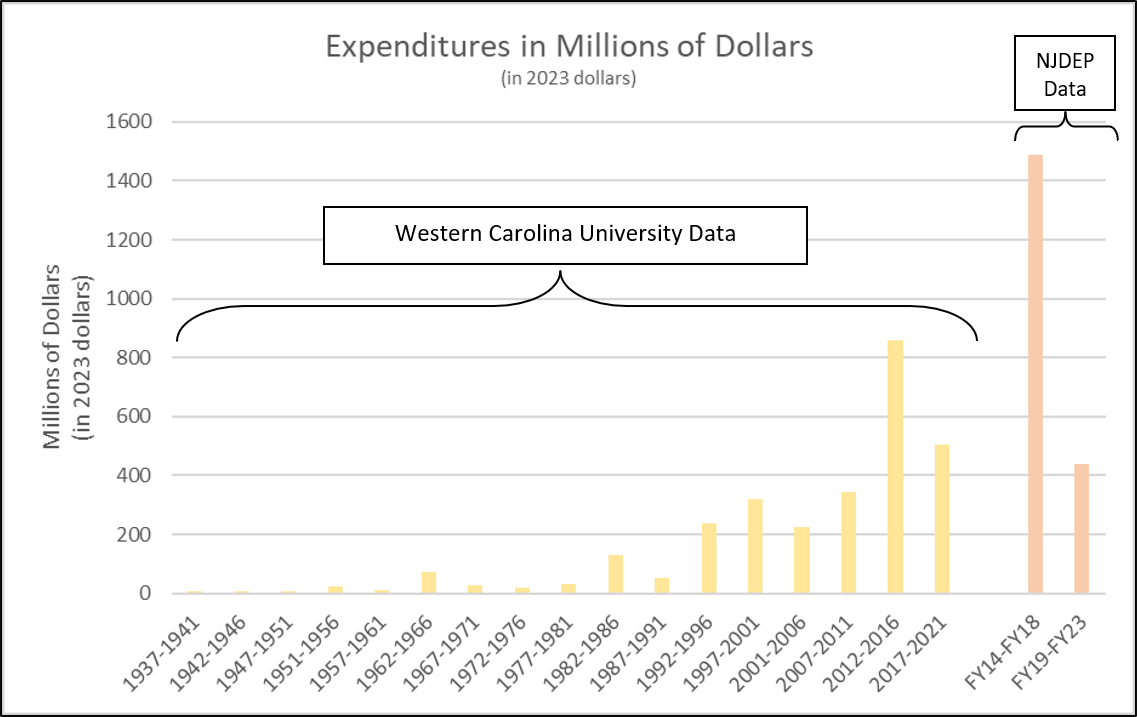

Replenishment of beaches with sand that is pumped or dredged from bay areas and from the ocean floor began in the 1930s. The quantities of sand placed on beaches and the associated costs have been collected through a comprehensive research project that covers twenty coastal states. The Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University (WCU) provided most past data evaluated for this report.8 These data are shown in Figures 1 and 2, “Beach Replenishment Volumes, New Jersey” and “Beach Replenishment Expenditures, New Jersey”. The NJDEP’s Office of Coastal Engineering augmented data compiled by WCU by providing two five-year summaries of the data, from FY2014 through FY2018 and for FY2019 through FY2023, shown in the last bars of each figure. Note that these two time periods overlap the summary periods provided by WCU and are based on fiscal years (FY, July – June) versus the calendar years provided by WCU. Data collected by both entities have some overlapping projects, but accounting methods and values differ which discourages comparisons. Trends seen within each data set are expected to be reliable.

Figure 1: Beach replenishment volumes in millions of cubic yards (CY), New Jersey

Figure 2. Beach replenishment expenditures in millions of (2023) US Dollars, New Jersey

The data shown in these charts indicate a general trend of both increasing quantities of sand deposited per unit time and increasing constant-dollar costs over time for the replenishment efforts. The number of projects in the state has increased, and an expanded area of the state is covered and now eligible for periodic nourishment. The last two bars in each graph represent data collected by NJDEP’s Office of Coastal Engineering and indicate that the West Carolina University data may not account for all replenishment projects managed by the NJDEP.

Outlook and Implications

As reported in the 2021 State of New Jersey Climate Change Resiliency Strategy, the State of New Jersey has spent over $1.2 billion rebuilding the barrier island beach and dune systems along the Atlantic Ocean coastline using funding from federal aid programs and the Shore Protection Fund’s $25 million annual state appropriation in response to the shoreline damage caused by Hurricane Sandy.9

Beaches are one of our nation’s most valuable resources. In addition to economic value, robust beaches play a significant role in maintaining a healthy coastal environment. As beaches erode, property, structures, and infrastructure are put at greater risk of damages from hurricanes and coastal storms. The importance and value of beach maintenance and replenishment projects will continue to grow in the face of rising sea levels.

While there is some concern that less funding may be available in the future for beach replenishment projects, NJDEP and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, as well as other state and federal agencies, are working on regional sediment management initiatives identifying additional suitable sand sources to ensure these projects continue to be sustainable and perform as designed. There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the financial feasibility question. As with construction costs across the country, the cost of beach renourishment has increased over the last several years. In some places, replenishment is needed, while in others, innovative nature-based approaches with multiple co-benefits like preservation, dune building, living shorelines, and thin layer placement are warranted. Additionally, proper operations and maintenance in between periodic nourishment cycles are vital to the success of these projects. Given the questions about future financial feasibility and availability of sufficient material, it is critical that the state and communities undertake comprehensive planning to consider the potential impacts to their vulnerability and resilience to increasing hazards from climate change.

Beach renourishment is one of many tools the state plans to employ in the coming years. In some areas resilience is provided by a beach and dune system. In other cases, it is elevations, flood walls, and tide gates. It is critical that each system is evaluated based on its unique nature and the community needs. Community education and planning plays a critical role in the selection of mitigation measures.

According to the best available science, rising sea levels coupled with the increased intensity of storms predicted by climate change models will result in worsening flooding and beach erosion over time. Education, community planning, funding for adequate periodic nourishment, and timely post-storm repairs are needed to maintain usable beaches and provide shore protection. Increased preparedness for floods and coastal damage will also be required.

A solid understanding of the latest climate science and forthcoming changes to our land resource protection rules is necessary to select the most appropriate approach to resilience. NJDEP will continue to work with federal partners to explore different methodologies, new technologies, and potential rule and policy changes to enhance our shorelines.

Going forward, it is critical that communities recognize and incorporate resilience into their planning. NJDEP has the expertise to address the immediate needs regarding sand on our beaches, however, our coastal communities must consider long-term adaptive management.10

More Information

Suggested Citation

NJDEP. “Beach Replenishment.” Environmental Trends Report, NJDEP, Division of Science and Research. Last modified October 2024. Accessed [month day, year]. https://njdepwptest.net/dsr/environmental-trends/beach-replenishment/.

Download the Data

The data used in Figures 1 and 2 are available to download here.

References

1Tourism Economics (Prepared for VisitNJ, posted) The New Jersey Visitor Economy 2022, March 2023. “The New Jersey Visitor Economy 2022”. https://visitnj.org/sites/default/files/2023-05/2022_Tourism_Economic_Impact_Study.pdf Accessed 1/24/2024.

2Kopp, R.E., C. Andrews, A. Broccoli, A. Garner, D. Kreeger, R. Leichenko, N. Lin, C. Little, J.A. Miller, J.K. Miller, K.G. Miller, R. Moss, P. Orton, A. Parris, D. Robinson, W. Sweet, J. Walker, C.P. Weaver, K. White, M. Campo, M. Kaplan, J. Herb, and L. Auermuller. New Jersey’s Rising Seas and Changing Coastal Storms: Report of the 2019 Science and Technical Advisory Panel. Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Prepared for the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Trenton, New Jersey. https://climatechange.rutgers.edu/images/STAP_FINAL_FINAL_12-4-19.pdf Accessed 6/24/2024.

3Farrell, Stewart, K. McKenna, S. Hafner, B Smith, C. Robine, H. Pimpinelli, N. DiCosmo, C. Tracey, I. Beal, A. Ferencz, M. Gruver, and M. Suran, 2017, An Analysis of Thirty Years’ Study of Sand Redistribution and Shoreline Changes in New Jersey’s Four Coastal Counties Raritan Bay, the Atlantic Coast, and Delaware Bay Fall 1986 Through Fall 2016, Volumes 1-4, Stockton University Coastal Research Center, 691 pp. https://stockton.edu/coastal-research-center/njbpn/reports.html, and https://stockton.edu/coastal-research-center/njbpn/documents/reports/MonCo2016.pdf Accessed 8/6/2024.

4Titus, James G., R.A. Park, S.P. Leatherman, J.R. Weggel, M.S. Greene, P.W. Mausel, S. Brown, C. Gaunt, M. Trehan, and G. Yohe, 1991, Greenhouse Effect and Sea Level Rise: The Cost of Holding Back the Sea. Coastal Management, 19, pp. 171-204.

5Hillyer, Theodore M., 1996, Shoreline Protection and Beach Erosion Control Study Final Report: An Analysis of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Shore Protection Program, Shoreline Protection and Beach Erosion Task Force, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Prepared for the Office of Management and Budget, 383 pp. https://www.iwr.usace.army.mil/portals/70/docs/iwrreports/96-ps-1.pdf, Accessed 6/26/2018.

6NJ Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), 1981, New Jersey Shore Protection Plan, Volumes I and II, NJDEP, Trenton, NJ

7State of New Jersey, Department of Environmental Protection, Land Use Management; http://www.state.nj.us/dep/cmp/index.html#njcmp, Accessed 8/6/2024.

8Western Carolina University (WCU), 2024. Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines. https://psds.wcu.edu/projects-and-research/beach-nourishment/ Accessed 8/5/2024

9State of New Jersey, 2021. Climate Change Resilience Strategy. https://njdepwptest.net/climatechange/resilience/resilience-strategy/ Accessed 8/5/2024.

10NJDEP, 2024. Preparing for Climate Impacts: https://njdepwptest.net/climatechange/resilience/ Accessed 8/5/2024.