In This Report:

Contact Us:

Minor edits on state delisting of bald eagles – Updated 1/2025

Environmental Trends Report

NJDEP, Division of Science and Research

Wildlife Populations-Bald Eagle

Background

The large, majestic bald eagle was selected as the U.S. national emblem in 1782 “as a symbol of strength, courage, beauty, and freedom.”1 During the nesting season, bald eagles are always found close to a water body where a ready supply of fish or waterfowl is available. They typically nest in old, large trees with a clear flight path on one or more sides, and often, a view of the water.2 The bird’s population in the lower 48 states decreased drastically in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, exemplifying the dangers of environmental contamination, loss of habitat, and illegal shooting of wildlife, and warning scientists of a loss of biodiversity throughout the world.

A major threat to the birds’ survival was increasing contamination of the environment after World War II with persistent chemicals such as DDT and PCBs.3 Accumulating in fish and other prey, these endocrine system-disrupting pollutants concentrated in eagles’ eggs and impaired hatching and nestling survival, primarily by weakening eggshells.3 Population numbers also were affected adversely by the loss of large areas of high quality contiguous forests and aquatic habitats, as well as human disturbance of eagles and other raptors during the sensitive nesting period. One study researched the last-known eagle nests in southern NJ, which were estimated to number 20 nests in the 1940s (Holstrom 1985). By the 1970s, however, the numbers had declined to a yearly average of one nest, and throughout that decade there is no record of the successful rearing of nestlings.

In 1972, DDT was banned in the United States, followed by bans of other pesticides such as aldrin, dieldrin, chlordane, toxaphene, and PCBs in the late 1970s and early 1980s.3 Subsequently, concentrations of these pollutants in the environment began to decline. At the same time, federal and state wildlife agencies instituted programs to protect and enhance bald eagle populations. The NJDEP Fish and Wildlife‘s Endangered and Nongame Species Program coordinated the state’s efforts to restore bald eagle populations. From 1983 through 1990, FW biologists monitored the release of 60 young eaglets obtained from Canada; it also coordinated intensive management of failing nests and protection of nesting sites by biologists and landowners.

Status and Trends

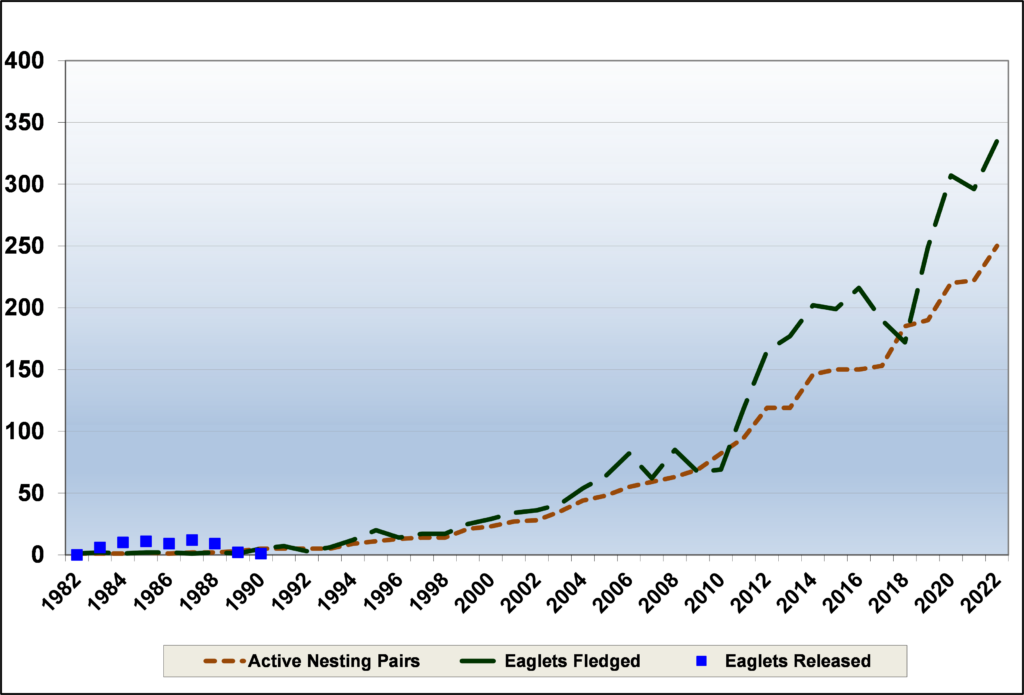

The steps taken to protect the bald eagle and foster its survival are paying off. Data assembled by Fish & Wildlife show a consistent increase in the bald eagle population in New Jersey over the last 30 years. In 2022, there were 250 active nesting pairs of eagles. One hundred and ninety-seven of these nests were successful in producing 335 young.4 (See Figure 1) About 16% of the known outcome nests failed to fledge young in 2022, a rate that is close to the 10-year average of 18%.

Figure 1: Population of nesting bald eagles and young in New Jersey

Outlook and Implications

In 2007, with a resurgence in the eagle population in most of the lower 48 states, the federal government removed the bald eagle from its list of Endangered Species.3 The US Fish and Wildlife Service is overseeing a 20-year monitoring period to watch for and investigate any problems that could compromise the eagle recovery.3 In January 2025, New Jersey updated the bald eagle’s official status from state-endangered to special concern. State regulatory protections are in addition to existing federal actions.3 It is important to note that the recent success in restoring the population of bald eagles has been due in part to active human intervention and protection. Continuation of such efforts by NJDEP Fish & Wildlife is planned and will likely be necessary for the foreseeable future.

The Delaware Bay region remained the state’s eagle stronghold, with roughly half of all nests located in Cumberland and Salem counties and the bayside of Cape May County.

Loss of habitat continues to be a problem, but encroaching development and disturbance by indiscreet observers may be the biggest problems currently faced by the bald eagle population in New Jersey.5 Some people, apparently unaware that their presence, may disturb the birds or may encroach on nesting areas which can upset and disrupt the birds’ behavior to the point where reproduction is impaired.

More Information

References

1 Simons, T., S. Sherrod, M. Collopy, and M. Jenkins, 1988, Restoring the Bald Eagle, American Scientist 76: 253-260, as referenced in Brauning, Daniel, (Ed.), 1992, Atlas of Breeding Birds in Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh and London.

2 Brauning, Daniel, (Ed.), 1992, Atlas of Breeding Birds in Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh and London.

3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Midwest Region, June 2007, Fact Sheet: Natural History, Ecology, and History of Recovery, https://www.fws.gov/midwest/eagle/recovery/biologue.html (Accessed 2/21/19).

4 Smith, L. and K.E. Clark, 2018, New Jersey Bald Eagle Project, 2018, Division of Fish and Wildlife Endangered and Nongame Species Program, https://njfishandwildlife.com/ensp/pdf/eglrpt18.pdf (Accessed 2/20/2019).

5 Niles, L., K. Clark, and D. Ely, 1991, Status of bald eagle nesting in New Jersey, Records of NJ Birds 17: 2-5.