Six Key Concepts

Elements of Resilience

- Resilience is the capacity of a community to “bounce forward.”

- Resilience results from processes that ensure diverse, equitable, and inclusive engagement of socially vulnerable populations.

- Resilience is fluid. It increases or decreases depending on circumstances. A catastrophic event or a financial, social, or health-related setback can reduce resilience. Social support can help an individual or community become more resilient.

Resilience is often defined as the ability of a community or individual to “bounce back” after hazardous events such as hurricanes, coastal storms, or flooding. But for many members of the community, returning to their previous situation may only serve to put them back in harm’s way, especially if social conditions make them vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Instead, as one observer put it, “the goal should be to come back stronger, better positioned for the future, to ‘bounce forward’” (Borenstein, 2014). Rather than simply surviving a disturbance, a resilient community responds in creative ways to fundamentally transform the community for the better.

For the purpose of this training, therefore, resilience is the capacity of a community to anticipate, plan for, eliminate, or reduce the dangers associated with changes in the environment and climate and, in doing so, seize resilience as an opportunity to address underlying social, economic, and physical factors in a community that may make a population more vulnerable to changing environmental conditions.

The process of building resilience involves making choices that can affect a community’s future. Decisions about what to protect and strengthen reflect deeply entrenched values and power structures. A comprehensive resilience plan must therefore incorporate the needs and perspectives of historically underrepresented and vulnerable populations. In fact, evidence clearly points to the fact that inclusive engagement of a community’s most vulnerable populations leads to more effective planning.

Resilience varies across populations. The ability to cope with a natural disaster depends on exposure to hazards as well as capacity to respond. Some people are more vulnerable to climate risks due to social factors such as age, socioeconomic status, health concerns, English-language proficiency, and access to transportation. Historically, socially vulnerable populations have also been underrepresented in political decision-making and public investment.

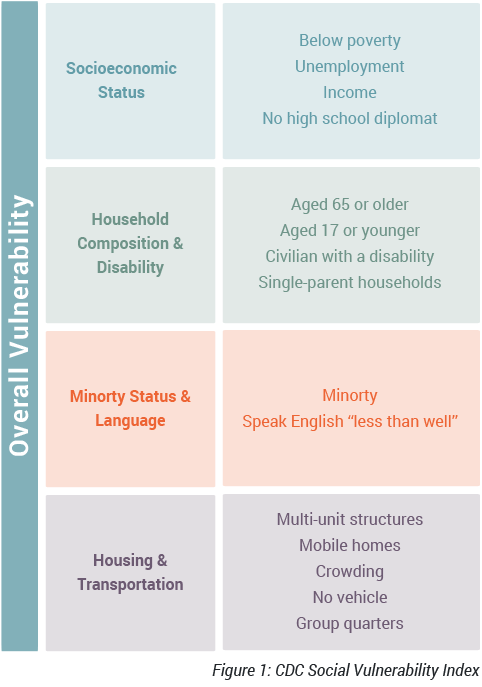

In an effort to identify populations that may need support responding to hazardous events, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) created a Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) that ranks every census tract on 15 social factors, including unemployment, minority status, disability, housing, and transportation. These social factors are grouped into four themes:

- Socioeconomic status

- Household composition & disability

- Minority status & language

- Housing & transportation

Research and recent events indicate that socially vulnerable populations are not limited to these categories. Increasingly, research and communities point to additional factors that may increase the inherent social vulnerability of a population, such as age of housing stock, environmental burden, veteran status, and community underinvestment. Several additional sets of data regarding social vulnerability, including age of housing stock, municipal distress, and ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) households, plus the CDC SVI, are reflected in NJ FloodMapper, an interactive mapping website to visualize coastal flooding hazards and sea level rise. More information on use of the CDC SVI and NJ FloodMapper are included in Unit 3 of this training.

While resilience planning and emergency management planning overlap in significant ways, they are not the same. In general, resilience planning takes a longer-term, more holistic view than emergency or disaster planning. It is grounded in the idea that creating healthy, equitable, and vibrant communities is the most effective way to build resilience. And, to do so, it’s essential to address the needs of the most vulnerable community members and to include them in the planning process.

Because socially vulnerable populations have been historically underrepresented in community decision-making, ensuring their involvement is critical to the development of comprehensive resilience plans. Historic underrepresentation in civic activities may make some groups or individuals distrustful of resilience planning processes, and challenges to their full participation may exist. Organizers should be prepared to proactively engage socially vulnerable residents rather than expect them to simply show up, even if invited. Units 2 and 4 of this training focus on strategies that resilience planners can use to create participatory processes to engage socially vulnerable populations.

The benefits of including socially vulnerable people are numerous and extend well beyond fair representation:

- The needs of the most vulnerable people may not be fully considered in the planning of response and relief organizations. Recent disasters are replete with examples of vulnerable people who appear to have been forgotten or “left behind” – e.g., low-income residents stranded in New Orleans without transportation after Hurricane Katrina, or seniors trapped in a Florida nursing home during Hurricane Irma. A resilience plan cannot be considered complete – and may be prone to critical omissions ¬– without the input of a community’s most vulnerable members.

- Socially vulnerable people have direct and detailed knowledge of their own situations and can offer unique insights into how best to address their needs.

- Some socially vulnerable groups are protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), ensuring individuals with physical, mobility, hearing, vision, speech, cognitive, intellectual, or mental health disabilities have the same civil rights protections as other Americans.

- Community resilience planning provides a forum for underrepresented populations to raise concerns, coordinate strategies, and secure commitments among government agencies, nonprofit organizations, businesses, and the public to advance equity goals in disaster planning and such related issues as economic development, environmental quality, housing, and infrastructure investment.

Whole-community resilience planning brings community members together for a common purpose, connects neighbors to each other, and creates opportunities for emerging leaders. This is especially true when the process includes members of marginalized or disempowered populations who might otherwise be disinclined or unable to participate. The planning process strengthens social cohesion, which, in turn, enhances resilience.

A whole-community approach to resilience planning encompasses the following values:

- Equality means that everyone is treated the same regardless of each person’s unique situation.

- Equity begins with recognizing that some people have an uneven “starting place” and that systems are needed to address or correct the imbalance to ensure that everyone, including socially vulnerable populations, has access to the same opportunities to be resilient.

- Diversity ensures that a variety of community voices are reflected in resilience planning and those voices accurately represent populations most affected by coastal hazards.

- Inclusion ensures that historically underrepresented populations, such as socially vulnerable people, are made to feel valued, encouraged to lead and grow, and given whatever support is needed to meaningfully participate in the resilience planning effort.