PLANNING FOR THE WHOLE COMMUNITY

Part One: The Whole-Community Approach

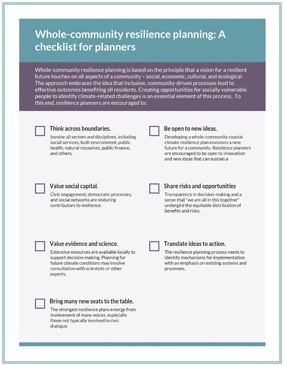

Whole-community resilience planning is based on the principle that a vision for a resilient future touches on all aspects of a community – social, economic, cultural, and ecological. The approach embraces the idea that inclusive, community-driven processes lead to effective outcomes benefiting all residents. Creating opportunities for socially vulnerable people to identify climate-related challenges is an essential element of this process.

Whole-community resilience planning goes beyond a response to short-term emergent natural disasters and, instead, seeks to build systems that increase the inherent capacity of a community to withstand trauma. Whole-community planning is also a valuable opportunity to reimagine a community in ways that are more vibrant, healthful, equitable, and prosperous. Doing so involves reaching across disciplinary and sectoral boundaries, bringing new voices into the conversation, and finding ways to spark innovation. To this end, resilience planners are encouraged to:

-

Download Whole-Community Resilience Planning: A Checklist for Planners Think across boundaries. Involve all sectors and disciplines, including social services, built environment, public health, natural resources, public finance, and others.

- Value social capital. Civic engagement, democratic processes, and social networks are enduring contributors to resilience.

- Value evidence and science. Extensive resources are available locally to support decision-making. Planning for future climate conditions may involve consultation with scientists or other experts.

- Bring many new seats to the table. The strongest resilience plans emerge from involvement of many voices, especially those not typically involved in civic dialogue.

- Be open to new ideas. Developing a whole-community climate resilience plan envisions a new future for a community. Resilience planners are encouraged to be open to innovation and new ideas that can sustain a community into the future.

- Share risks and opportunities equally. Transparency in decision-making and a sense that “we are all in this together” undergird the equitable distribution of benefits and risks.

- Translate ideas to action. The resilience planning process needs to identify mechanisms for implementation with an emphasis on existing systems and processes.

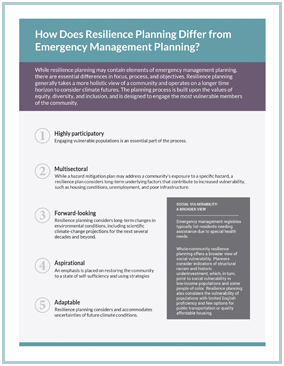

Download How Does Resilience Planning Differ from Emergency Management Planning? Resilience planning is sometimes confused with hazard mitigation and emergency management planning. Hazard mitigation planning is the process of reducing risks and impacts from natural and man-made hazards. Emergency management directs community response to disaster and emergency events in order to minimize risk to people and assets.

While resilience planning may contain elements of emergency management and hazard mitigation, resilience planning generally takes a more holistic view of a community and operates on a longer time horizon to consider climate futures. The planning process is built upon the values of equity, diversity, and inclusion, and is designed to engage the most vulnerable members of the community. Specifically, resilience planning is:

- Highly participatory. Engaging vulnerable populations is an essential part of the process.

- Multisectoral. While a hazard mitigation plan may address a community’s exposure to a specific hazard, a resilience plan considers long-term underlying factors that contribute to increased vulnerability, such as housing conditions, unemployment, and poor infrastructure.

- Forward-looking. Resilience planning considers long-term changes in environmental conditions, including scientific climate-change projections for the next several decades and beyond.

- Aspirational. An emphasis is placed on restoring the community to a state of self-sufficiency and using strategies that promote multiple community benefits, such as natural infrastructure.

- Adaptable. Resilience planning considers and accommodates uncertainties of future climate conditions.

Socially vulnerable populations typically listed in emergency management registries are residents who need immediate assistance due to physical or developmental disabilities, people with special health needs (including mental health), and senior citizens.

Resilience planning can complement emergency management and hazard mitigation planning by offering a broader view of social vulnerability. For example, whole-community resilience planning considers indicators of structural racism and historic underinvestment in certain communities, which, in turn, point to social vulnerability in low-income populations and some people of color. Resilience planning also considers the vulnerability of populations with limited English proficiency and few options for public transportation or quality affordable housing. Recent climate-related events in the mid-Atlantic region and elsewhere have underscored the vulnerability of immigrants and people with mental health conditions.