Shellfish Aquaculture in New Jersey

Aquaculture is a water dependent form of agriculture involving the propagation, rearing, and subsequent harvesting of aquatic organisms in controlled or selected environments, and the subsequent processing, packaging, and marketing. This may include, but is not limited to, activities to intervene in the rearing process to increase production such as stocking, feeding, transplanting, and providing for protection from predators.

For the purposes of this website, shellfish only refers to molluscan bivalve shellfish (e.g., oysters, clams, mussels) and does not include gastropods (snails) or crustaceans (crabs, shrimp). Currently, the primary focus of aquaculture in New Jersey waters is cultivation of two species of bivalve shellfish, hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) and oysters (Crassostrea virginica).

Shellfish aquaculture in New Jersey can be divided broadly into two main categories: 1) non-structural or traditional on-bottom shellfish culture; and 2) structural aquaculture that uses gear or equipment to contain the shellfish. For both categories of shellfish culture, the activity occurs on a Commercial Shellfish Lease or Riparian authorization that expressly allows the activity.

Non-Structural Aquaculture

Non-structural aquaculture is a more traditional type of culture that allows a leaseholder to grow shellfish using methods that mimic a shellfish bed.

For example, a leaseholder may harvest wild oysters and transplant them to favorable growing locations and/or place clean shells on the seafloor of a lease to capture

wild oyster recruitment (shell planting). Typically, traditional oyster aquaculture is used to move various sized oysters to areas with faster growth and better survivability. This method of oyster aquaculture has a long history within New Jersey’s portion of Delaware Bay and the Mullica River system.

Hard clam aquaculture in New Jersey is also considered a traditional form of aquaculture. One option— similar to that of oyster culturists— involves harvesting wild hard clam stocks and transplanting them onto a lease that is better for growth and survival of the hard clams. A second non-structural method for growing hard clams uses hatchery-reared seed planted at a smaller size within a lease. Due to predation concerns, hard clams are covered with predator screens throughout the full production timeline. In New Jersey, hard clam aquaculture is found within the Atlantic Coastal Bays.

Traditional aquaculture often requires fewer permits and licenses (relative to the use of structure) since these culture activities are recognized as environmentally benign.

Structural Aquaculture

In more recent years, the use of structure to culture shellfish has gained popularity among New Jersey shellfish growers. The use of structure to manipulate the growth, appearance and marketability of oysters has become more profitable as more consumers demand a unique half-shell product. It requires more work from the grower but also, generally, yields a higher price. The following are examples and descriptions of the most commonly used structural aquaculture practices.

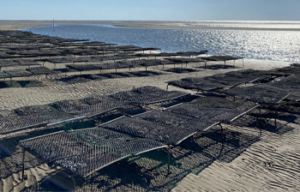

Rack and Bag

- Systems consist of steel rebar racks that support and elevate mesh bags off of the bottom. These rack systems are typically laid out in rows separated by

alleyways (or lanes) at least as wide as the racks themselves to allow access for tending the structures and the oysters. - This gear can be found within intertidal areas of Delaware Bay.

Bottom Cage

- The size of cages depends on a grower’s need and size of operation. Some growers use cages that are approximately 3-ft x 3-ft x 4-ft high in dimension,

while other growers use cages that are nearly 10-ft x 10-ft x 8-ft high in dimension. The cages are generally equipped with small legs that aid in

providing some clearance between the bottom and the cage. - In Delaware Bay, bottom cages are deployed in deeper waters and as such are typically larger than those on the Atlantic Coast. They are placed into subtidal

areas and tended by boats equipped with either cranes or winches. - In the Atlantic Coastal Bays, smaller and lighter cages are generally deployed in shallower waters and tended by smaller vessels.

Suspended or Floating Culture

- Suspended or floating aquaculture systems utilize hanging bags, cages, and/or floats on or near surface waters.

- This method may also be used in the intertidal or subtidal zones and includes a wide range of practices.

- This method is used in varying degrees throughout all New Jersey growing waters but generally in lower energy areas.

Nursery Systems

- Seed from a hatchery may be too small to place directly onto the seafloor or into a grow out system. Instead many growers opt for a nursery system to get

the seed larger before placement onto a lease. - In a nursery system the seed has access to a constant flow of food and water, promoting rapid growth.

- These systems can be land-based (upwellers) or in the water, typically connected to land. A common system is called a Floating Upweller System (or FLUPSY),

which resembles a section of dock. The main difference is that a FLUPSY has upwellers (seed held in buckets with mesh at the bottom, water flowing up

through the bucket and out the top) contained underneath the wooden boards.

Additional Considerations

The placement of shellfish on a lease is not the end of the process for shellfish aquaculture. Growers must ensure their gear is cleaned of sediment and other fouling organisms (e.g., sponges, mud worms (polydora) and algae) and shellfish are sorted and spread into new gear as they grow and need more space. Often market-ready shellfish are placed into a separate section of the farm to ensure safe harvest of the product.

For hard clam growers, the time to harvest can be anywhere from three years up to five years depending upon the environmental conditions and desired size. Oysters typically grow to market size faster, anywhere from one and a half years to just under three years. Growers of all species of shellfish must have several year classes growing to ensure they always have product ready to sell.

Finally, at harvest, the growers must ensure they follow best management practices and state level regulations. Shellfish are alive until they are cooked or shucked, and must be kept cold to discourage bacterial growth until they reach the consumer.

OFFICIAL SITE OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY

OFFICIAL SITE OF THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY